“If we accept there is no such thing as ‘zero risk’ then we should not spin the meaning of words with assertions such as ‘all accidents are preventable.’ – Dr. Rob Long

In terms of process safety, one definition of risk is, “[The] combination of the frequency of occurrence of harm [the likelihood] and severity of that harm [the consequence].” This definition paints the picture that to have risk, you have to have a hazard that you are concerned about.

While going through the safety lifecycle, some might introduce hazard analysis prior to discussing how risks can be addressed. I take a more unconventional approach. There is no disputing that in order for risks to be addressed, hazards must be identified, or that hazards are identified during a Process Hazard Analysis (PHA); however, in order to complete a PHA, a Risk Tolerance Criteria (RTC) table based on a company’s defined tolerable risk levels has to first be developed. How do you know if your company’s is better than others? What are the results if your company’s RTC doesn’t follow a conventional approach? What even is the ‘conventional approach’?

What is Tolerable Risk?

What makes one company’s risk tolerance criteria better than another’s? A big key to answering this question centers on the nomenclature and understanding of what risk really is. The terminology of risk rests on two ideas: the physical injury or damage that occurs in an event (the consequence), and the probability of that event (the likelihood). Risk is about events that may or may not happen in the future. Managing risks is about estimating the harm that may occur in the future and the likelihood of its occurrence.

Before we can begin to address risk, we must first identify the hazards we are concerned about. These hazards are typically addressed during the PHA. After the hazards are identified, a risk assessment can be performed during which a team evaluates the likelihood and consequences of a hazardous scenario occurring.

We can only deduce if the risk of a hazard is too great by comparing it against some kind of standard or collected criteria – the risk tolerance criteria (RTC) – which is the basis for deciding if a risk is too high. Many organizations judge risk against a single RTC. If the risk is below the RTC, nothing more needs to be done about it. If the risk is above the RTC, it must be reduced. This gap, or residual risk, between the inherent risk and the RTC, is the basis for safety integrity level (SIL) assignment. The bigger the gap, the bigger the SIL. This is why developing reasonable RTC upfront is crucial.

Zero Risk

Before working with your team to develop or revise your company’s RTC, it’s important to understand that there is no such thing as zero risk. The goal of reducing risk to zero is not only unreasonable, it is impossible. We can only reduce the risk of an activity to zero by avoiding the activity entirely, but then we just substitute a different activity with its own risks. For example, we can risk twisting our ankle when we get out of bed in the morning, but if we don’t get out of bed, we risk getting bedsores.

Risk with no reward is called “pure risk,” and people rarely undertake these. This might look something like flying in an airplane knowing beforehand that the aircraft has had significant engine problems and hasn’t been repaired. Risk with at least the potential for reward is called “speculative risk” and is part of everything we do. We tolerate the risks because we believe the benefit of an activity outweighs the risk.

The idea that risk can be reduced to something that is tolerable, however, is something that is achievable.

Important Questions to Ask

In order to assess whether your company’s RTC makes sense, or when establishing RTC for the first time, it is important to ask the following questions:

- Are the likelihood categories separated by equal orders of magnitude?

- Are the impact categories (safety, community, environmental, assets) relevant?

- Are the impact categories separated by equal orders of magnitude?

- Are the impact categories for different receptors (impact vectors) aligned?

- Are the impact categories benchmarked to tolerable frequencies?

- Are risk rankings assigned uniformly?

These questions help provide a solid foundation for your company’s RTC.

What does this ‘conventionally’ look like?

In a typical likelihood category set, the frequency of the event occurring is based on a log-log scale, separated by equal orders of magnitude:

> once per 10 years

> once per 100 years

> once per 1,000 years

> once per 10,000 years

< once per 10,000 years

Since risk is the product of likelihood and consequence, both frequency and impact must be considered. Most of the time, RTC looks at the impacts to safety, community, the environment, and sometimes assets. For example, a people-personnel impact category set might look something like the following:

≥ a first aid treatment

≥ a recordable injury

≥ a permanently disabling injury

≥ a fatality

≥ 10 fatalities

This assignment is done for each of the impact categories your company might have. When two or more impact categories have the same tolerable frequency, they are equivalent, whether intended or not. This is why it is very important that impact categories are aligned with care.

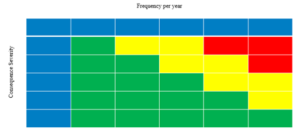

Figure 1 – Example of a risk tolerance matrix

Once the likelihood and consequence have been established over a log-log scale, a risk matrix can be created (as seen in Figure 1 for use in your company’s PHA and LOPA (Layer of Protection Analysis)). Having a risk that is tolerable for each consequence, represented on this matrix with green boxes, helps adequately allocate resources. Without a tolerable frequency for each consequence impact, no matter how many additional protection layers your company adds, the risk will not be reduced to an acceptable level. The only additional risk reduction measure would be elimination of the scenario entirely and elimination is not always a feasible option.

How is Risk Reduced?

What if your company’s risk is too great? The simple answer is to reduce it through Risk Management. To reduce risk, either the likelihood of the hazardous event must be reduced or the consequence of the hazardous event must be reduced, or a combination of both. In practice, there are two fundamental ways to reduce risk: prevention and mitigation.

You can do this through a variety of different methods, such as passive protection, better procedures/policies, mechanical protection, control systems, or Safety Instrumented Systems (SIS). Each of these examples is either a preventative measure to reduce risk or a mitigation measure to reduce risk.

The purpose of prevention is to reduce the likelihood of a hazardous event occurring. For instance, a no smoking policy at a gas station will reduce the likelihood of a fire. If a fire does break out though, a no-smoking policy will not have any effect on how bad the fire is. On the other hand, the purpose of mitigation is to reduce the consequence of such a hazardous even, should it occur. If the owner of the gas station purchases fire insurance, the financial consequences of a fire will be much less, but owning insurance will not do anything to reduce the likelihood of a fire starting.

RTC and Going Forward

When a company has reasonable RTC established, they remove the need for excess or unreasonable risk to be reduced. This means that their company not only has a more realistic idea of the likelihood and consequences during a PHA and LOPA review but also that their company will not be overspending in order to put risk reduction measures in place where they aren’t necessarily needed. Using the five questions above, you and your company can work your way through creating or verifying your company’s RTC. Are there questions there that you’re unable to answer? Are there areas your company needs to change to make your RTC more effective? Specific questions you’d like to ask us? Let us know in the comments.

During the next step of our safety lifecycle discussion, we will take an in-depth look at hazard analysis so that we can identify the hazards which we are trying to protect against. We’ll use the knowledge we learned here about RTC and discuss it during our review of PHAs.