“If you can’t take the heat, get out of the kitchen.” — Harry S. Truman

For decades, I’ve told people that OSHA requires thermal protection on surfaces over 140°F (60 C) up to a height of 7 feet. People just accepted that because a) I was the expert and b) it made sense. Recently, though, I began to wonder, where exactly does OSHA say that?

It doesn’t. Not exactly.

So why are so many safety specialists convinced that OSHA requires personnel protection from thermal exposure to surfaces over 140°F (60 C) up to a height of 7 feet?

The August 19, 1998, Letter of Interpretation

On August 19, 1998, John B. Miles, Jr., Director of the Directorate of Enforcement Programs, wrote a letter to Mr. Mike Lodge of Procedair Industries that OSHA then posted as a standard letter of interpretation. The letter is now obsolete and archived “as historical content, for research and review purposes only.” In this letter, Mr. Miles confirmed that there is no specific OSHA standard nor guidelines to determine the temperature of metal pipe that should be insulated to avoid burning skin on contact, but says that OSHA considers “exposed heated surfaces, if there is a potential for injury, to be a hazard and will issue citations if employees can come into with such surfaces.”

The Seven-Foot Rule

Mr. Miles then pointed to two industry-specific regulations.

The first was the standard for Pulp, Paper, and Paperboard Mills, 29 CFR 1910.261, which says in 1910.261(k)(11) that “all exposed steam and hot-water pipes within 7 feet of the floor or working platform or within 15 inches measured horizontally from stairways, ramps, or fixed ladders shall be covered with an insulating material, or guarded in such manner as to prevent contact.”

The second was the standard for Textiles, 29 CFR 1910.262, which says in 1910.262(c)(9) that “all pipes carrying steam or hot water for process or servicing machinery, when exposed to contact and located within seven feet of the floor or working platform shall be covered with a heat-insulating material, or otherwise properly guarded.”

The two requirements are not exactly the same (apparently textiles don’t have to worry about the 15-inch horizontal requirement), but they are specifically about steam and hot water (temperature not defined) pipes to a height of 7 feet. In the textile industries and the pulp, paper, and paperboard industries, specifically, but no where else.

OSHA could make the seven-foot rule a general requirement, but they haven’t. Instead, they rely on the general duty clause, which requires that employees be protected from recognized hazards.

The 140°F (60 C) Rule

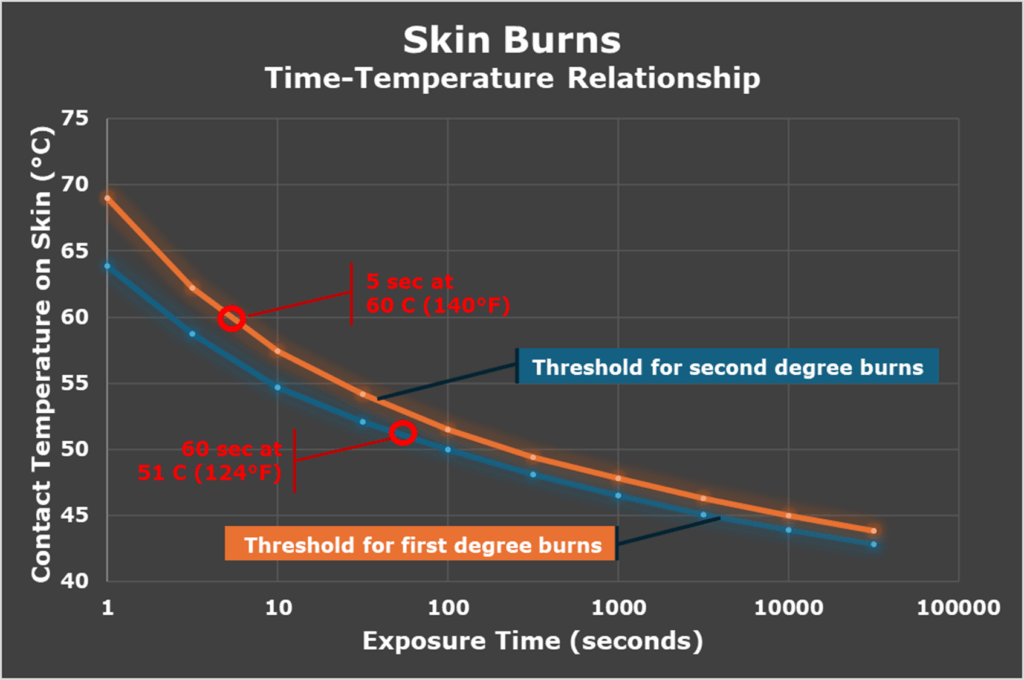

The 1998-Aug-19 letter of interpretation explicitly states that there is no OSHA standard in regard to the temperature at which pipe is considered too hot to touch. It did, however, mention the American Society for Testing and Materials’ (now officially known as ASTM International) Standard Guide for Heated System Surface Conditions That Produce Contact Burn Injuries, C 1055. Figure 1 in that standard shows the temperature-time relationship for burns.

ASTM Standard C 1055 makes two assumptions for the sake of discussion: In the case of infants and domestic appliances, it assumes that “no more than first degree burns in 60 seconds might be desirable.” In the case of experienced adults and industrial equipment, “second degree burns in 5 seconds might be acceptable.” A look at the figure below, which is based on the information in C 1055, shows that the temperature that results in first degree burns in 60 seconds is 51 C (124°F) while the temperature that results in second degree burns in 5 seconds is 60 C (140°F).

Figure 1. The time-temperature relationship for first and second degree burns and contact with hot surfaces.

The ASTM committee made the leap from “might be acceptable” to a firm recommendation. Then, voilà, a rule is born.

But not an OSHA rule.

Degrees of Burn Injuries and OSHA

But OSHA does consider second degree burns as the threshold for serious injuries…right?

Not so much.

A first degree burn only affects the thin outer layer of skin called the epidermis. The skin is red with no blisters. First degree burns, though painful, rarely result in long-term damage.

A second-degree burn penetrates the epidermis into the thicker underlying layer of skin called the dermis, where there are blood vessels and nerves. The skin is red, blistered, and swollen.

A third-degree burn penetrates the dermis to damage the muscles, tendons, and even the bones underneath. The skin is charred or white and there is no pain because the nerves are destroyed.

There is a widely held belief that second-degree burns are recordable injuries, and according to C 1055, a second-degree burn results from contact with 140°F (60 C) surfaces that last for 5 seconds. In some belief systems, the second-degree burn must be bigger than a dime to be recordable.

What does OSHA require?

OSHA’s website has a section where they answer frequently asked questions. One of the questions they address is “Does the size or degree of burn determine recordability?” Here is their answer:

“No, the size or degree of a work-related burn does not determine recordability. If a work-related first, second, or third degree burn results in one or more of the outcomes in section 1904.7 (days away, work restrictions, medical treatment, etc.), the case must be recorded.” –OSHA

There Are Citations For Burns

Real understanding of OSHA’s expectations come less from what they say, however, and more from what they do. Here are examples of OSHA citations for contact burns and for exposure to hot surfaces to be aware of:

Citation 314206822/01001 “Employees were exposed to hot metal pipes which are housed on the pasteurized machine and are heated up to approximately 185°F.” Cited under the general duty clause.

Citation 312530389/01001 “a) Mixing area – The two low melt pipes running close to the wall had never been insulated, exposing hot surfaces at 165°F. b) Mixing area – The hot oil pipes and fittings running close to the floor between tanks 7 and 8 were partially insulated, exposing hot surfaces at 175-185°F.” Cited under the general duty clause.

Citation 1615812.015/01002 “The employer did not ensure employees working near the Rotating Molder Chiller machine #1 were protected from severe burn hazards due to potential contact with non-insulated and/or unguarded boiling water or steam pipe. This pipe, at approximately 210°F, ran along the edge of the machine, and was easily accessible via accidental contact.” And “the employer did not ensure employees working near the Rotating Chiller machine #5 were protected from severe burn hazards due to potential contact with non-insulated and, or unguarded boiling water or steam pipes. The pipes, at approximately 135°F and 195°F, ran along the edge of the machine, and were easily accessible via accidental contact.” And “the employer did not ensure employees working or traveling around the ‘steam cabinet’ in the whey area were protected from severe burn hazards due to potential contact with non-insulated and/or unguarded boiling water or steam pipes and fixtures. The pipes and fixtures, measured between approximately 93°F and 288°F ran along the wall of a thoroughfare, and were easily accessible via accidental contact.”

Threshold Temperatures

Any discussion of contact burns should mention two temperatures that are thresholds for burns. The first is the lower threshold temperature of 43 C (109°F). This is the temperature below which even an “infinite” contact time will not result in any skin injury. The second is the upper threshold temperature of 70 C (158°F), the temperature above which contact with metallic surfaces will instantly result in thermal injury to skin.

Good Places to Start, But Not the Last Word

While it’s convenient to have hard and fast rules about when hot surfaces must be insulated or otherwise protected, they are not OSHA rules. It’s not as though 141°F is hazardous, but 139°F is non-hazardous, or that people cannot reach above 7 feet. OSHA expects workers to be safe from thermal exposure, wherever it is. The 7-foot and 140°F rules are good places to start, but they are not the end of the hazard assessment.