“Paper doesn’t save people. People save people.” — Dan Peterson

I don’t know anyone in a regulated community that likes regulations. Some may accept them because they bring clarity in a confusing situation, but no one likes them. Even with the best of intentions, someone that must comply with a lot of regulations worries that they will inadvertently screw up and be subject to a citation.

I take comfort in knowing that most safety regulations actually serve to make the workplace safer. I can read a regulation and say, “Yeah, I get it. We will be safer when we do this.”

So, it infuriates me when regulations that are supposed to be about safety don’t make things safer, or worse, make things less safe.

The March 11 Changes to the RMP Rule

On March 11, 2024, the EPA’s final amendments to the RMP rule hit the books. The amended rules became effective on May 10. There are dozens of changes to the rule, but three have gotten the most attention:

- The requirement for STAA – safer technology and alternative analysis, in PHAs

- The requirements for RCA – root cause analysis, in incident investigations

- The requirement for third party compliance audits, which is now a whole new element of compliance.

Compliance will not be a trivial undertaking, and the operators of covered processes have three years – until May 10, 2027 – to comply. Many expect that some, if not all, of the amendments will not survive judicial scrutiny, so it will be interesting to see which actually go into effect. But as I said, compliance will not be a trivial undertaking, so I don’t advise waiting for these regulations to go through the courts before beginning work on complying with them.

One of the lesser changes hasn’t got much attention, though, and it won’t be delayed. That is the requirement to retain hot work permits for three years. It is really disappointing, though. Not because it will be hard to do, but because it does absolutely nothing to improve safety. We’ll spend time and energy on this instead of on something actually makes us safer.

About Hot Work Permits

Both the OSHA Process Safety Management (PSM) Standard, 29 CFR 1910.119, and the EPA Risk Management Planning (RMP) Rule, 40 CFR 68 have a section called “Hot work permit”. The RMP rule has it because the PSM standard had it before the RMP rule was written. The PSM standard has it because…

Why does the PSM standard include hot work permits as one of its 14 elements?

Both the PSM standard and the RMP rule refer to 29 CFR 1910.252(a), Welding, Cutting and Brazing, General Requirements, Fire prevention and protection. It’s a good rule, full of measures that will make hot work safer. And since it already exists as a standalone, enforceable regulation, why does it need to be mentioned in other regulations?

I always assumed that it was so that a hot work permit violation would allow OSHA to cite non-compliance twice: once for non-compliance with 29 CFR 1910.252(a), and once for non-compliance with 29 CFR 1910.119(k).

It turns out that there is a difference between the two regulations, though.

In 29 CFR 1910.252(a)(2)(iv), where OSHA discusses authorization and hot work permits, the regulation says “Before cutting or welding is permitted, the area shall be inspected by the individual responsible for authorizing cutting and welding operations. He shall designate precautions to be followed in granting authorization to proceed preferably in the form of a written permit.” [emphasis added] In 29 CFR 1910.252(a), written hot work permits are optional!

In the PSM standard, OSHA makes written hot work permits mandatory. It also expands the definition of hot work beyond “cutting and welding” to include brazing and “similar flame or spark-producing operations.”

The Purpose of Hot Work Permits

The original purpose of hot work permits, as envisioned in the Welding, Cutting, and Brazing regulations, was to assure that the individual authorizing the hot work inspected the area beforehand. The permit is not what makes the work safer. The inspection is what makes the work safer.

A written permit serves to create a checklist, so that when the individual authorizing the hot work does their inspection, they are reminded of what to look for. It also serves to communicate to the individuals performing the hot work the measures that must be in place and remain in place while they perform their hot work.

It makes sense, then, that OSHA’s requirement is that the permit needs to be kept “until completion of the hot work operations.” Because after the hot work operations are complete, there is no hazard.

Hot Work Permit Retention

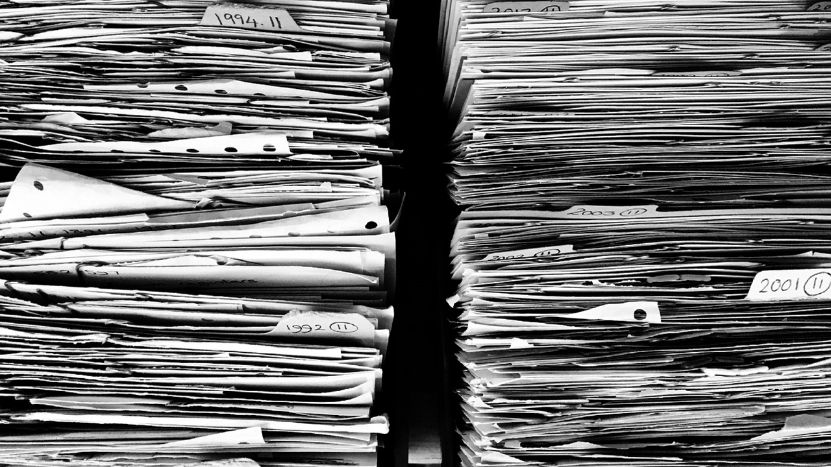

Some organizations developed the habit of hanging on to expired or cancelled hot work permits. When the filing cabinets started to overflow, they began stacking bankers’ boxes full of old permits in storage closets. We have a name for this: “Fire Hazard.” Eventually, someone posed the question: How long do we need to keep these old permits?

OSHA answered the question in a 12-Dec-2006 letter of interpretation to E.C. Palmer: “The PSM standard does not require employers to maintain a file of old or closed hot work permits… The permit shall be kept on file until completion of the hot work operations.”

In the same letter of interpretation, however, OSHA did walk that back, at least when it came to compliance audits. “OSHA expects that employers would audit a statistically-valid number of hot work permits to assure they were completed and implemented per their procedure… One way to audit hot work permits to evaluate compliance with 29 CFR 1910.119(k) is to complete the audit before the permits are discarded.”

So, even as OSHA expressed concern about compliance audits, they didn’t require extended retention. They just want employers to make sure that compliance with the hot work permit element is audited before tossing the permits. If an employer chose, that could be done on a monthly basis. There is no need for boxes and boxes of old and closed hot work permits in a closet somewhere.

The Tail Wagging the Dog

The EPA isn’t even pretending that retaining expired hot work permits makes for a safer facility or reduces the likelihood of a release to the environment. Regulations themselves rarely explain why the regulation is necessary. They just say what to do. Explanations are found in the Federal Register when an agency announces the new regulations. And in the announcement for these new regulations, the EPA telegraphs its intentions by including its discussion of the new hot work permit retention requirement in the section on “Enforcement Issues.” There, they come right out and say, “Under existing RMP regulations, it can be difficult for implementing agencies…to determine if the facility has been conducting hot work in compliance with the requirements of 40 CFR 68.85.”

This rule is not about making facilities safer. It’s about making it easier for inspectors to write citations. It’s a case of the tail wagging the dog.

1095 Days

Some of the things we do make us safer. Some of the things we do bring us into compliance with regulations. And occasionally, some of the things we do accomplish both. This is not one of those times. But it would be silly to be cited for failing to keep file cabinets stuffed full of expired and closed hot work permits, whether they have been reviewed and audited, or not. So, start saving them. But not for more than 1095 days.