“The battle of getting better is never ending.” — Antonio Brown

There’s an old joke about someone looking for their keys under a streetlight. A passerby offered to help but after a while, asked, “Are you sure this is where you lost them?”

“No, I lost them over there in the park.”

“Then why are we looking here?”

“Because the light is better.”

The joke captures an idea now known as the Streetlight Effect.

The Chemical Process Industries Are Getting Safer

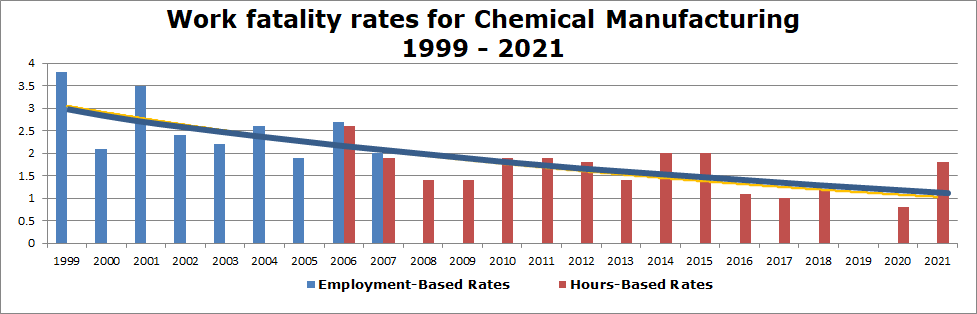

Since 1999, safety in the chemical process industries, as measured by fatality rates, has been improving. Not steadily, not smoothly, not consistently, but the trend is clearly downward. Much of that improvement is because of the intense focus we’ve placed on process safety since OSHA first promulgated the PSM standard in 1992. The Streetlight Effect.

We should worry, though, that the chemical process industries are so focused on process safety concerns as the cause of injuries and fatalities in the workplace, because that is where the light is better, that we are overlooking what have now become graver concerns. The work-related fatality rate for the chemical process industries has been falling. The fatality rate for the CPI in 1999 was 3.8 fatalities per 100,000 workers. In the most recent data from the Bureau of Labor Statistics (BLS), the fatality rate for the CPI in 2021 was 1.8 fatalities per 100,000 full time equivalents (FTEs).

If the trend continues, we’ll see a trending fatality rate of 1 fatality per 100,000 FTEs in 2022 (a rate we’ve bested twice already, in 2017 and 2020), and a rate of 0.5 fatalities per 100,000 FTEs in 2040.

But safety doesn’t improve spontaneously. It requires dedicated effort to bring it down. The question, then, is about where we should be devoting that effort.

Where Have the Improvements Come From?

The BLS characterizes work-related fatalities as being caused by one of six types of events:

- Transportation-related

- Falls, slips, and trips

- Contact with objects and equipment

- Violence and other injuries by persons or animals (primarily homicides)

- Exposure to harmful substances or environments

- Fires and explosions

Every year, they report this data for the economy as a whole. They also publish tables that break it down by industry. The economy as a whole gets an almost complete accounting of the breakdown. For instance, the BLS assigned 5,172 work-related fatalities to one of the six types of events, out of a total of 5,190 work-related fatalities in 2021. The BLS breakdown by industry is often not as complete. In 2021, for instance, the BLS reported 58 work-related fatalities in the CPI (NAISC codes 324, 325, and 326), but only assigned 47 of them to a specific type of event. Although incomplete, the industry data is still illuminating.

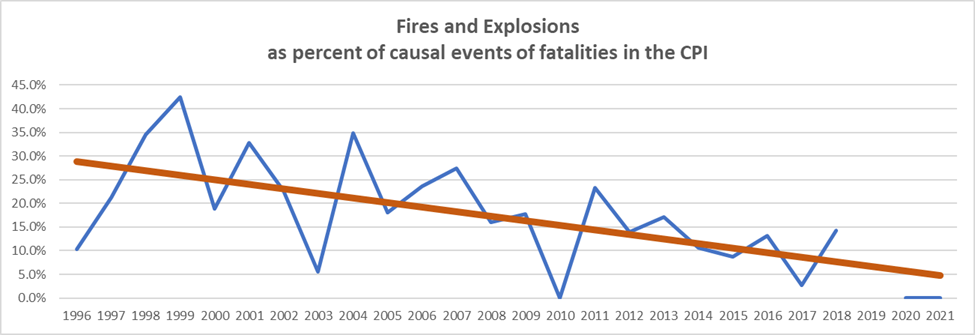

In the late 90’s, fires and explosions accounted for about 30% of the work-related fatalities in the CPI. Since then, probably due to our emphasis on process safety, fires and explosions now account for less than 5% of work-related fatalities in the CPI. The improvement is all the more impressive when considering that ~30% of 3 fatalities per 100,000 workers is ~0.9 fatalities per 100,000 workers in the late 1990s. Compare that to ~5% of 1.8 fatalities per 100,000 FTEs in 2021, or 0.09 fatalities per 100,000 FTEs. There is not relatively much left to squeeze from fires and explosions.

What about the other five types of events?

Where Are Additional Improvements Unlikely to Come From?

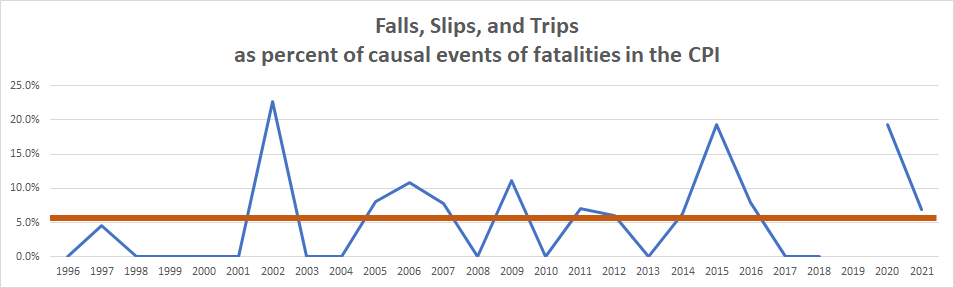

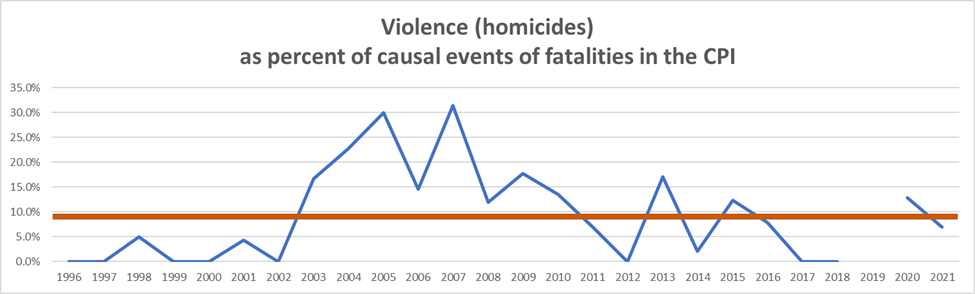

Most types of events have shown no obvious trends in how they lead to work-related fatalities in the CPI.

Falls, slips, and trips, for instance, have been up around 20% of work-related fatalities in the CPI in some years (2002, 2015, 2020) but down at 0% in many other years (1996, 1998, 1999, 2000, 2001, 2003, 2004, 2008, 2010, 2013, 2017, 2018), with an average of 5% over the years. For planning purposes, it has always been as low as fires and explosions have become. It was not an event in the 1990’s that should have jumped to the top of our list of areas of concern. It is still not.

Workplace violence is similarly without an obvious trend. It has been as high as 30% of work-related fatalities in the CPI in some years (2005, 2007) but as low as 0% in many other years (1996, 1997, 1999, 2000, 2002, 2012, 2017, 2018), with an average of 9% over the years. Again, not an event that should have jumped to the top of our list of areas of concern, and still not an event that should jump to the top of our list of concerns.

Where May Additional Improvements Come From?

There are a couple of event types that suggest some opportunity for safety improvement in the CPI.

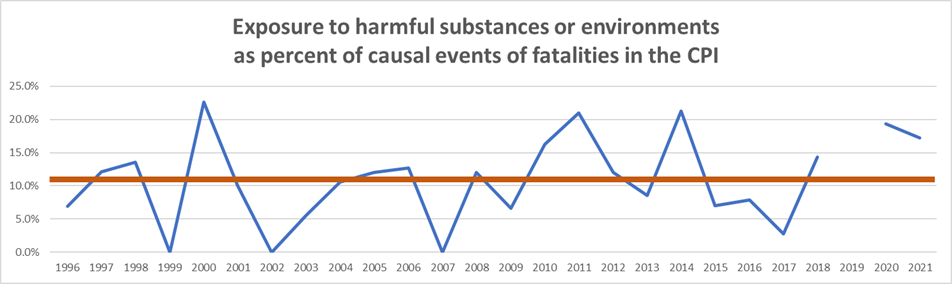

Exposure to harmful substances or environments hints at an upward trend as the cause of work-related fatalities in the CPI. Before 2005, it exceeded 20% of work-related fatalities in the CPI once (2000), but twice in the years since (2011, 2014). Conversely, before 2005 it was 0% in two years (1999, 2002), but only once in the years since, and that was in 2007. Over the years, exposure events, which include electrocution and drug overdose, have accounted for an average of 11% of fatalities in the CPI. This may be an event that is becoming one of increasing concern to the CPI, something we should pay closer attention to and be ready to respond with risk reduction efforts.

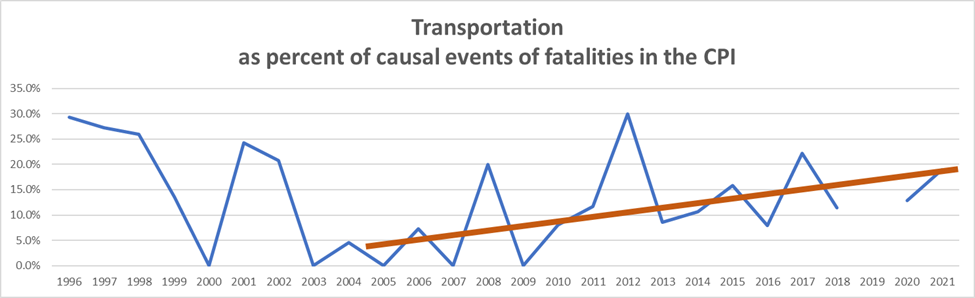

Likewise, transportation also hints at a slight upward trend, especially since 2005. Before 2005, it approached 30% of work-related fatalities in the CPI once (1996). Since 2005, it reached 30% of work-related fatalities in the CPI once again (2012). The year 2005 is also the dividing year between years with 0% of fatalities in the CPI: in 2000, 2003, and in 2005, and then in 2007, 2009. Over the years, transportation events have accounted for an average of 14% of fatalities in the CPI. Considering the possibility that there has been an upward trend for the past 16 years, it appears that transportation-related fatalities in the CPI are another concern that deserve our attention. We don’t want to drift back to where we were in the 1990s because of neglect.

The Greatest Potential for Improving Safety in the CPI

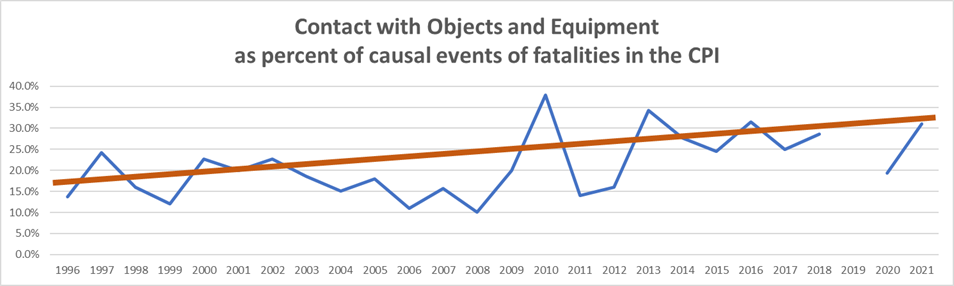

While falls, slips, and trips and work-related violence are not likely to be the events where there is relatively much opportunity for improvement, and exposure to harmful substances or environments and transportation hint at opportunities for some improvement, there is one type of event that is more and more often the cause of work-related fatalities in the CPI:

Contact with Objects and Equipment.

In the 1990s, when fires and explosions were the most significant cause of fatalities in the CPI, contact with objects accounted for about 15% of fatalities in the CPI, compared to the 30% accounted for by fires and explosions. In the years since, as the fraction of fatalities caused by fires and explosions has fallen, the fraction of fatalities caused by contact with objects and equipment has risen. In fact, the rise in the fraction of fatalities caused by contact with objects and equipment has shown more constancy than any other type of event. And in no year for which there are readily accessible records has the fraction ever been 0%.

Let’s Shine the Light Where the Hazards Are

The key to making the CPI safer is looking where the hazards are, not necessarily where the light is brightest. The regulatory environment has shone a spotlight on process safety, particularly fires and explosions. As an industry, we should take great pride in the progress we’ve made there. At the same time, we should not relax. Continued vigilance will keep us from backsliding.

Continued dedication to process safety will keep it from getting worse after so many years of improvement, but it won’t lead to the new improvements in safety that we all want to see happen. The improvements are going to come in the areas where we’ve made little relative progress, in the areas that have received little light. Events like exposure to harmful substances and environments and like transportation hazards.

The real progress, however, is going to come from tackling the hazard of contact with objects and equipment. These aren’t chemical hazards, but these are the hazards that are killing our workers. This must be the next field to get the bright light of safety’s attention.