“If they knew it was water-reactive, why did they store it in a warehouse with automatic sprinklers?” — Chris Schmidt, retired pre-school teacher

Wikipedia is a “go-to” source for quick information. Regarding the fire at the BioLab facility in Conyers, Georgia, however, it has this disclaimer: “Information may change rapidly as the event progresses, and initial news reports may be unreliable.” Meaning, a lot of what we’ve heard about the incident is wrong, and unfortunately, Biolab has not been very forthcoming. We will know a lot more after the Chemical Safety Board (CSB) completes its investigation and publishes its report. That will take months, however, and there are lessons we can learn from the incident now.

What Happened in Conyers?

At about 5 am on Sunday morning, September 29, 2024, a fire started on the roof of the product storage warehouse of the Biolab facility in Conyers, a town about 25 miles east of downtown Atlanta. They got the fire put out.

Biolab personnel then began removing product from the warehouse. Press accounts describe the product as a dry, water-reactive chemical, but don’t identify it. However, previous incidents at Biolab, both at its Georgia facility and its Louisiana facility, suggest that it was trichloroisocyanuric acid (TCCA) or a mixture containing TCCA. They hadn’t completed their work when the fire reignited, setting off automatic sprinklers in the warehouse. The water reacted with the TCCA remaining in the warehouse, generating a thick orange and black plume of smoke. The fire itself was finally brought under control by 4 pm on Sunday afternoon, but reaction with water continued to feed the plume.

Recognizing that the plume contained chlorine gas, chloramine, and other chlorine compounds, authorities ordered thousands of residents to shelter in place and closed portions of Interstate 20. Authorities reopened the interstate on Monday morning, September 30, and lifted the shelter-in-place order on Monday night.

There have been no injuries.

What is TCCA?

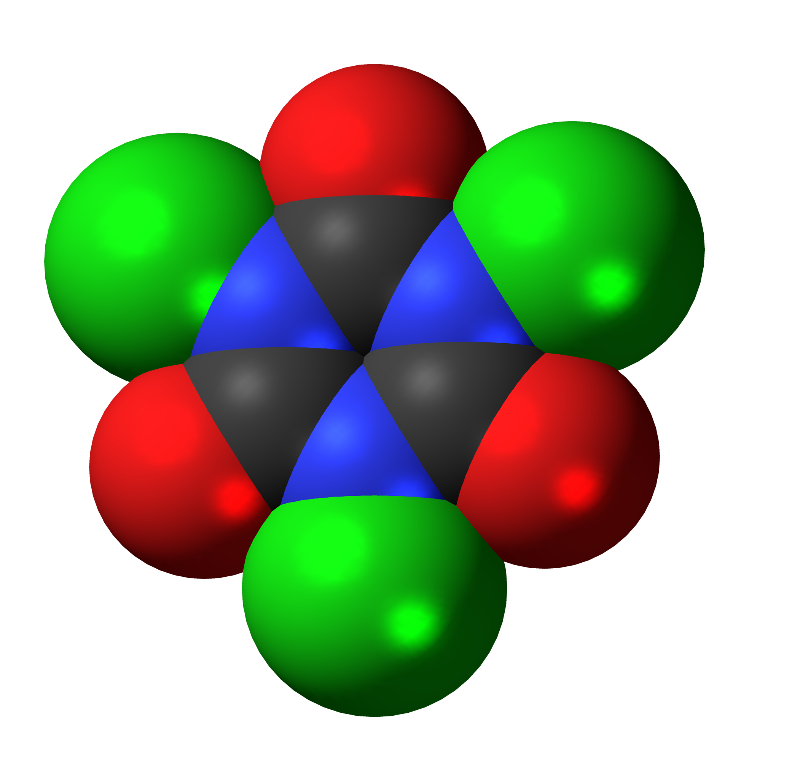

TCCA, with the chemical formula C3Cl3N3O3, has the IUPAC name of 1,3,5-trichloro-1,3,5-triazinane-2,4,6-trione. Yeah, it’s a mouthful. Let’s stick with calling it TCCA.

TCCA is a white crystalline material, often formulated in a granule or tablet form for use as an algicide, a bactericide and a disinfectant in swimming pools and spas. Contrary to the EPA’s characterization, it is not an insecticide. Its advantages as a swimming pool treatment chemical, especially when compared to chlorine, is that it is a solid rather than a gas, and that it dissolves slowly, releasing chlorine into the water as it does. It is much, much safer than chlorine and has become essential to reducing the waterborne diseases associated with untreated pool water.

Wait! TCCA is a pool treatment chemical, but it is described as “water-reactive?” In truth, it does not appear in the list of water-reactive chemicals in the U.S. Department of Transportation Emergency Response Guidebook.

An SDS for TCCA recommends that as extinguishing media, “flood with copious amounts of water.” The SDS describes TCCA’s reactivity as “Not reactive under normal temperatures and pressure” and its stability as “Stable at normal temperatures and pressures.” It does state that as a Possibility of Hazardous Reaction: “Do not get water inside container. Wet material may generate nitrogen trichloride, an explosion hazard.” However, the section on Incompatibilities/Materials to Avoid does not mention water.

How do we reconcile the apparent discrepancy? Is TCCA water-reactive or not? The CSB report on the August 2020 BioLab incident at their Lake Charles, Louisiana facility does a good job of explaining:

In large bodies of water, the TCCA formulation is soluble and breaks down slowly, releasing available chlorine in the water to sanitize contaminants. When a TCCA-based formulation instead comes in contact with or is wetted/moistened by a small amount of water and does not dissolve, it can experience a chemical reaction, generating heat and causing the decomposition of the chemical, which in turn produces toxic chlorine gas and can produce explosive nitrogen trichloride.

So, flooding a fire with TCCA makes sense. A little bit of water, however, will make things worse.

Why Store in A Warehouse With Automatic Sprinklers?

In its investigation report on the Lake Charles incident, the CSB identified five main safety issues. Under the heading, Emergency Preparedness and Response, the CSB complained of a “largely nonfunctional fire protection system and the absence of automated sprinkler systems.” [emphasis added]

Under the heading, Adherence to Applicable Hazardous Materials Codes, the CSB noted that BioLab did not provide the safeguards expected for high-hazard industrial occupancies in NFPA 101, The Life Safety Code, which requires “automatic extinguishing systems or other protection to minimize danger to occupants before they have time to evacuate”, nor did it conform to NFPA 400, Hazardous Materials Code, which requires “a fire detection system and an automatic fire sprinkler system.” [emphasis added]

So, it appears that a warehouse with automatic sprinklers is a requirement of NFPA codes, the lack of which prompted the CSB to raise concerns. But was an automated sprinkler system the right choice? Given the need for copious amounts of water, it seems as though a deluge system would be a better choice.

What’s Next?

Much has been made recently of BioLab’s history of incidents. Here are a few:

On May 25, 2004, a warehouse fire at the Conyers facility and resulting plume led to an evacuation of residents within a mile downwind of the facility. No one was injured, but runoff of fire water caused a fish kill at a local lake.

On August 27, 2020, high winds from Hurricane Laura damaged the Lake Charles facility, allowing rainwater to contact TCCA and resulting in a plume that led to closing I-10. There were no injuries.

On September 20, 2020, an incident where water reacted with a dozen pallets of TCCA stored at the Conyers facility resulted in shutting down I-20 for six hours. Rockdale Fire spokesperson Jamie Leavell said of the incident: “There were no flames, but there was heat involved.”

With this incident, many in the community have run out of patience. The Guardian headlined its article “Pattern of negligence,” quoting a resident, and reported that a petition, “Shut Down Bio Lab in Conyers,” has already collected more than 1,500 signatures. At least 6 lawsuits have already been filed.

Local officials may be very friendly to businesses that provide employment and contribute to the tax base. Ultimately though, they want to be reelected, and they know that won’t happen in the face of an organized resistance by their citizens. Their support will fade. For companies that loose the support from a community’s residents and official will find staying in business increasingly untenable.

Déjà Vu All Over Again

At the most fundamental, we all need to realize that an SDS is the starting point for understanding the hazards of the chemicals that we work with, not the last word. I wouldn’t blame anyone who reads the SDS for TCCA to come away not realizing that getting it wet would lead to closing nearby interstates and causing tens of thousands of people to shelter in place. But this ain’t BioLab’s first rodeo. The report that the CSB issues for Conyer in 2024 is going to bear an uncanny resemblance to the report they issued for Lake Charles in 2020.

A community will have limited tolerance for an incident that impacts them directly—their ability to drive to work, to leave the house, to breathe. It doesn’t require deaths or injuries, just widespread inconvenience. We all operate with the blessing of the communities we are in. If we lose that, we lose our permission to operate, regardless of the permits we have.

Do you understand the hazards of the chemicals you are using, their potential to have widespread impacts? Do they have a history? We only learn from experience, but it doesn’t have to be our own experience.

Leave A Comment