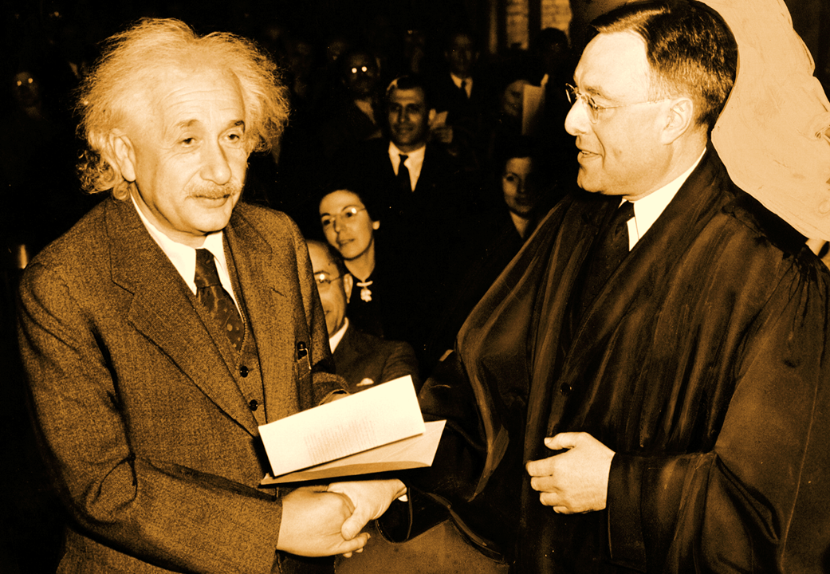

“If you can’t explain it simply, you don’t understand it well enough.” — often misattributed to Albert Einstein

I don’t spend much time in court rooms. I’m not a lawyer. I tend toward law-abiding behavior, so I’ve not been a defendant. I refuse to be an expert witness. (Lawyers seem to want me to follow a script.) What gets me into a court room is jury duty.

While I would prefer not to be summoned, it’s my civic responsibility. Unfortunately, the City of St. Louis hosts a lot of trials, so many of its citizens get called every 28 months, the statutory limit.

I just served on a jury in a trial that relied on several expert witnesses. It was a reminder of how important it is to explain things simply.

Keeping It Simple

One of the witnesses was a young police officer. He referred several times to his FTO, and no one ever asked him to explain that acronym. I’m a process safety engineer, so I’ve experienced my share of acronyms, but I didn’t know this one. Flameless Thermal Oxidizer? Fluorinated Tin Oxide? Flexible Time Off? As a juror, I was under strict orders not to do any research or look things up (even definitions) but when the trial was over, I discovered that the officer probably meant Field Training Officer.

Another witness was the medical examiner (ME). As anyone who has ever spent time with medical professionals knows, that profession has more acronyms than engineering or law enforcement. Combined. But they also have technical terms. For instance, “ecchymosis.” What’s that, you ask. Well, I now know that the ME (see what I did there) could have said “contusion” if they felt compelled to use a word with several syllables. Or they could have just said “bruise.”

The most egregious abuse of jargon, however, was when a crime scene technician described images in photographs as “ballistic damage to a vehicle.” It seemed to me that the technician could have said “bullet holes in the car” and been more descriptive to the group of people—the jury—that needed to understand. Fortunately, the photographs spoke plainly where the technician did not.

Acronyms as Shorthand

Three years ago, my colleague, Michael Smith, wrote a blog about the jargon that process safety professionals rely on. He led his piece with a quote from Kingman Brewster: “Incomprehensible jargon is the hallmark of a profession.” However, Michael’s piece was less about jargon than it was about acronyms. In a 1,500-word essay, Michael managed to mention 29 separate acronyms: PSM, OSHA, API, ISA, IEC, NFPA, P&ID, PFD, PHA, PSSR, MOC, HazOp, RAGAGEP, PSI, MI, LOPA, QRA, SRS, SIS, BPCS, SIL, SIF, BMS, HIPPS, IPL, PFD (again), EPA, RMP, OCA.

The thing about acronyms, however, is that they are just shorthand for terms that take longer to say and to spell out in a document. It’s easier to say or write “PSM” than to spell it out as “Process Safety Management”. Fewer syllables, fewer keystrokes. There is nothing about these acronyms that seeks to disguise the meaning of a term, to keep it secret from the uninitiated. Nothing that an initial definition—you know, like Process Safety Management (PSM)—and a glossary can’t address.

Jargon as Disguise

Jargon can occur when we take an ordinary word with a range of meanings and assign it a specific, narrow technical meaning. In that case, jargon allows practitioners to be more precise. But unless we practitioners take the time to define our jargon to those who are not members of our secret club, they won’t understand what we are talking about.

The thing we need to be more concerned about is when we use jargon to disguise our meaning. I once wrote about “rapid unscheduled disassembly” and “uncontrolled decomposition”, both of which are euphemisms for “explosion.” Why would we say this? Because it hides our meaning. It takes something terrible and makes it softer, less harsh.

Keep It Simple

When we’re working with employees or the public, our terminology can create a barrier. That barrier to communication is bad for safety and undermines everything we say and do. Telling a worker that it is important to do a certain thing “or else you may suffer a life-threatening injury” is not nearly as effective as saying “or else you will die.”

The point of language is to communicate. When our use of acronyms or jargon clarify what we’re talking about, that is helpful to communication. But when our use of acronyms or jargon create a barrier to understanding, we no longer communicate.

So, let’s be careful. Not everyone with whom a safety professional communicates is another safety professional already steeped in the language of safety professionals. Life is hard enough. Let’s not make it any harder than it has to be, for our colleagues or for the people we serve. To keep it safe, let’s also keep it simple. (Also not said by Einstein.)