“Fentanyl is everywhere. From large metropolitan areas to rural America, no community is safe from this poison.” — Anne Milgram

I believe that we cannot reduce the number and rate of work-related fatalities if we do not understand what causes them. So, every December I study the annual statistics for work-related fatalities when the Bureau of Labor Statistics publishes them for the previous year. The BLS categorizes work-related fatalities as being caused by one of six types of events. Transportation is the leading cause, regularly accounting for about 40% of all work-related fatalities.

There are two types of events of special interest to those of us concerned about process safety:

- Exposure to harmful substances or environments (harmful exposure), and

- Fires and explosions.

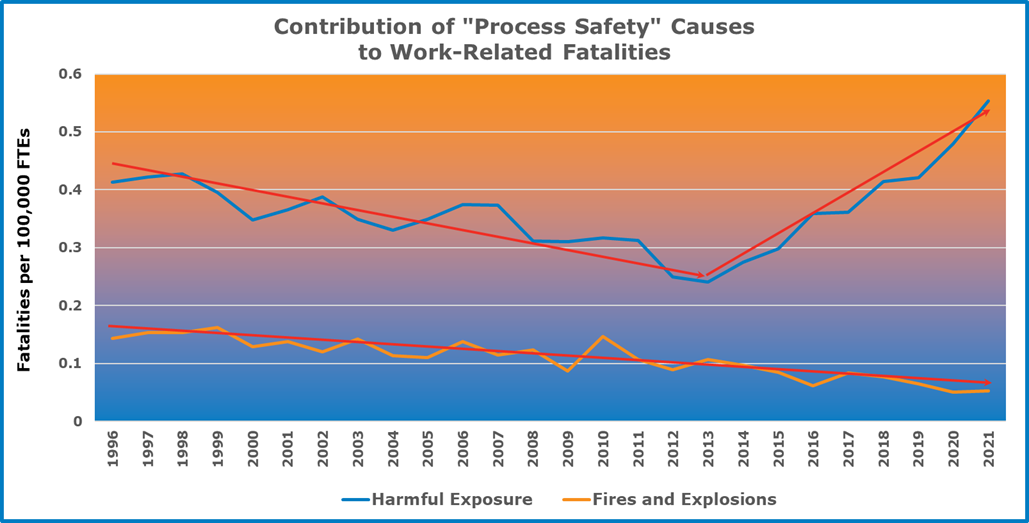

As a percentage of all work-related fatalities, there has been a significant shift fatality rate resulting from harmful exposure. That means something has changed. Understanding that change is key to understanding the cause. Otherwise, we won’t know what to do about it.

Fires and Explosions, Harmful Exposures

Not all fires and explosions occur in the process industries. Nor do all harmful exposures occur in the process industries. But they are reasonable surrogates for the kinds of hazardous events we in the process industries worry about. Since 1996, which is as far back as the data is readily available, the contribution of fires and explosions to the overall fatality rate in the United States has been falling. Why? Better fire safety, better fire training, less acceptance of fires and explosions as a normal cost of business, and perhaps, the promulgation of OSHA’s Process Safety Management standard (29 CFR 1910.119) in 1992. The rate has continued to fall. None of us look too closely at good news. Whatever we’re doing differently, it’s working. We should keep doing it.

As with fires and explosions, the contribution of harmful exposures to the overall fatality rate in the United States fell from 1996 to 2013. In fact, it fell at twice the rate that the contribution by fires and explosions to overall fatality fell, perhaps because it was starting from a higher rate.

Something happened in 2013, however. Instead of continuing its fall, or even levelling out, the contribution of harmful exposures to the overall work-related fatality took a sudden and sharp upward turn. It is now higher than it has ever been.

What Happened?

Exposure to harmful substances and harmful environments includes drowning, simple asphyxiation, and electrocution. It also includes drug overdoses at work.

When the BLS released the data for 2021 in December 2022, the accompanying press release included this statement: “Exposure to harmful substances or environments led to 798 worker fatalities in 2021…increasing 18.8% from 2020. Unintentional overdose from non-medical use of drugs or alcohol accounted for 58.1% of these fatalities deaths.”

Unintentional overdose accounted for 464 of the 5,190 work-related fatalities in 2021. That was a fatality rate of 0.32 fatalities per 100,000 full-time equivalents (FTEs), more than the work-related fatality rate associated with harmful exposure in 2013, and more than the work-related fatality rate ever associated with fires and explosions.

Why?

Fentanyl.

Fentanyl is Everywhere

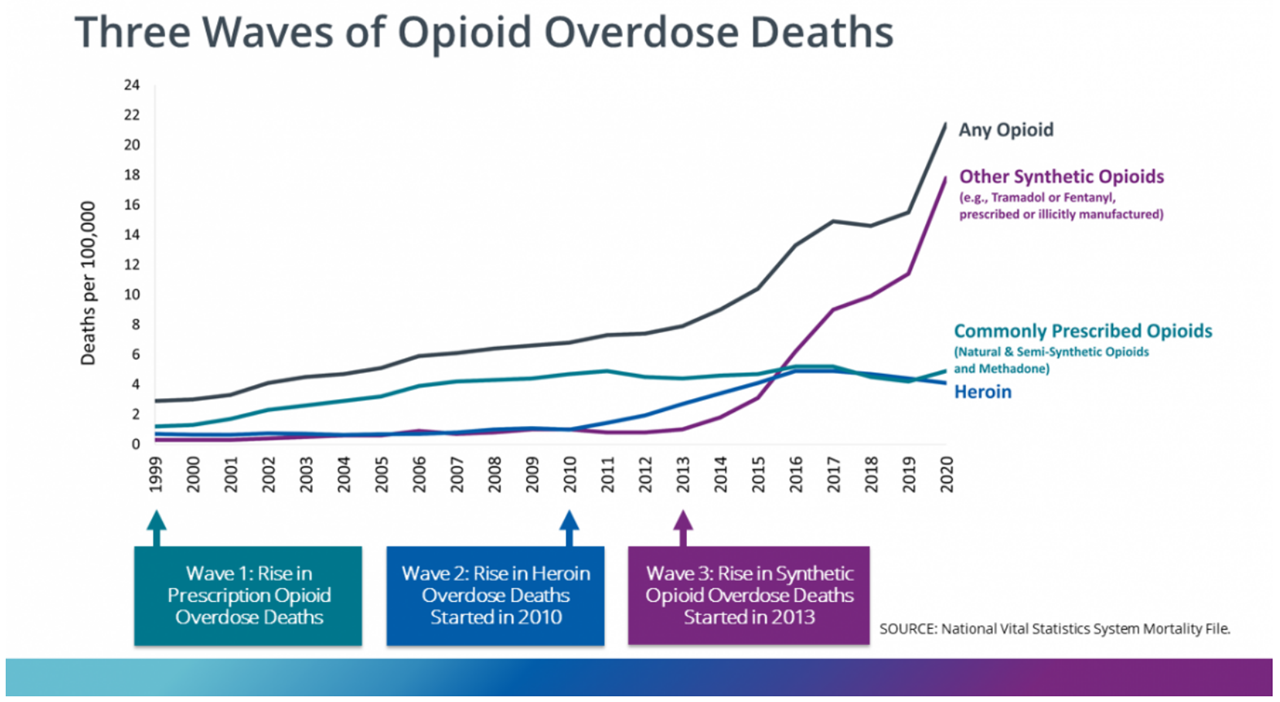

The Center for Disease Control (CDC) recently published “Understanding the Opioid Overdose Epidemic.” It describes three waves of opioid overdose deaths. The first began in 1999 as a result of doctors over-prescribing opioids to manage pain. The second began in 2010 when people suffering from addiction increasingly turned to heroin (which had been in decline as a drug of choice) because it was less expensive and more readily available than prescription drugs. Both of these waves, however, were mere ripples compared to the third wave, the tsunami of fentanyl that began in 2013.

By 2020, opioid overdoses were killing over 22 people per 100,000 people, of which there were 0.32 work-related fatalities per 100,000 FTEs.

What Can We Do?

Preventing illicit drug use or abuse is a complex problem that involves discouraging use, limiting supply, and addressing the root causes of addiction. Preventing fatal overdoses is much simpler. The drug, Narcan (the trade name for naloxone) reverses the effects of opioid overdose. Naloxone works whether the overdose is the result of natural opioids, like opium, morphine, and codeine; semi-synthetic opioids like heroin; or synthetic opioids like methadone, oxycontin, tramadol, and fentanyl.

Naloxone works by bumping opioids from the opioid receptors in our brains, and blocking their re-uptake, typically for 60 to 90 minutes. When someone is suffering an opioid overdose (signs include unresponsiveness or unconsciousness, fingernails or lips having turning blue or grey, slowed or stopped breathing or heartbeat), spray naloxone can be administered by squirting into their nose and injectable naloxone can be injected into a large muscle in the arm, thigh, or buttocks.

Then, if they have stopped breathing, it is important to give them rescue breaths (like CPR but without chest compressions). Meanwhile, someone should call 9-1-1.

Think of it as A-B-C: Administer naloxone, Breath for them, Call 9-1-1.

Does Narcan Enable Drug Abuse?

Some worry that having naloxone available will enable opioid abuse, even encourage it. They believe that the threat of overdose is an important deterrent to abuse. By analogy, then, the presence of a first aid kit should be seen as encouraging scrapes, scratches, burns, and knocked out teeth. This way of thinking would suggest that the presence of an AED – an automated external defibrillator – will encourage people with unhealthy diets to have a second serving of fried chicken wings with ranch dressing at the company luncheon. Really? “Don’t keep a fire extinguisher around. It only encourages people to set things ablaze,” said no one, ever.

People who use opioids already know about the threat of overdose. If anything, the presence of naloxone kits is a constant reminder of the threat of overdose. Also, it is a reminder to employees struggling with opioid addictions that their co-workers care about them.

Add Naloxone to Your First Aid Kit

Opioid overdose is not someone else’s problem, it’s everyone’s. In our years in the chemical process industries, we’ve known a few people in chemical plants who suffered from substance use disorders (SUDs). Often, it resulted from overtreating pain after an injury. Because there is a stigma attached to SUDs, we have no doubt that for every person we’ve known with SUD, there are another dozen who were unwilling to tell us about theirs. Is there someone at your facility with an SUD? Probably. If they overdose at work, their problem becomes your problem.

For naloxone to work, it must be administered. To be administered, it must be available. So, add naloxone to your first aid kit. Our offices are Cherokee Street in south Saint Louis, a neighborhood that The Riverfront Times once described as “the hippest neighborhood in Saint Louis. (Obviously, the average hipness of the neighborhood went down when a bunch of process safety consultants moved in.) But as a result, there are vending machines on the street where we can get Narcan spray at no charge and we have a neighbor, Mo Network, who is nearby and gives Narcan training at no charge. Even without these resources, however, Narcan is now available over the counter. But there are resources. Everywhere, if you just look for them. Look for them. Add Narcan to your first aid kit. You can save a life.