“The entire health care system is now being organized around machines instead of human beings. Not prioritized to reduce human suffering, but rather to optimize a computerized recordkeeping system. This is a tragedy.” — Carolyn Jourdan

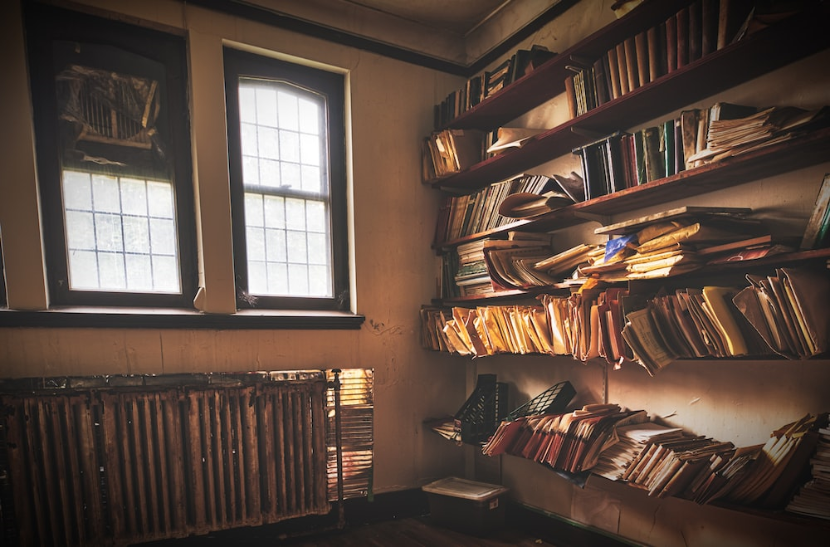

Imagine for a moment that you are a new PSM coordinator. The person who had the job before you is leaving for a long-awaited retirement and is not going to be available to consult with. On their last day, just before their retirement party, but after they’ve cleaned out their desk, they point to a scary, cob-webbed room known as “The Crypt”. “This is all the PSM documentation. It may not be complete, but this is all of it.”

You look in horror at stacks and stacks of paper files. Was the departing PSM coordinator a hoarder, or do you need all this stuff? Is there anything missing? Is there anything you can get rid of?

In your heart, you know the answer is “yes” to all of your questions, which is really no help. Where do you start?

Start With the Regulation

The Process Safety Management Standard, 29 CFR 1910.119, calls for written documentation and in some cases, it calls for document retention. There are fourteen elements of the PSM standard, so it would be reasonable to expect that the standard calls for at least fourteen types of written documentation. Nope.

c) Employee participation – You need a written plan of action for employee participation. Make sure you’ve got one of those, and that it addresses all fourteen elements. You don’t need to keep previous revisions. The most current version will do.

d) Process safety information – The standard requires several types of information. Making sure that you have it all will probably be the most daunting task you face.

e) Process hazard analysis – The standard requires that PHAs and updates or revalidations, as well as the documented resolution of recommendations be retained for the life of the process. Yes, for the life of the process. If the PHA from 1996 is missing, you don’t meet the letter of the standard, and unfortunately, it’s not as though you can recreate it.

f) Operating procedures – These must be readily accessible, which should be understood to mean written (although this can be in an electronic format). They must be certified at least annually that they are current and accurate. That word, “certified”, suggests a certificate—a written document, but there is nothing in the standard that states that obsolete operating procedures and any but the most current certification must be retained.

g) Training – A record of training must be prepared which contains the identity of the employee, the date of the training, and the means used to verify understanding. Nothing in the standard states how long you must retain this record.

h) Contractors – The standard has a lot of requirements in regard to contractors, but only one requirement for written records: you must maintain a contract employee and illness log related to contractors’ work in process areas. Not a word about how long to keep this log.

i) Pre-startup safety review – Amazingly enough, the standard requires that a PSSR check on many items in relation to a new or modified process but is absolutely silent on the subject of written documentation or retention of those documents.

j) Mechanical integrity – The standard requires written procedures for mechanical integrity procedures, but there is no requirement to retain obsolete procedures. The standard also requires written documentation of each test and inspection performed on process equipment. How long to retain those test and inspection reports? Not stated.

k) Hot work permits – The requirement is that the permit “shall be kept on file until completion of hot work operations.” Since most hot work permits expire at the end of a shift, that means that the requirement is to keep them for no more than 12 hours. So why do you find a file cabinet full of the hot work permits issued for the last 10 years?

l) Management of change – The standard calls for a written procedure to manage change. Great. What about the changes themselves? Only by understanding the term “procedure to manage change” to mean the forms that are completed in the course of managing change can OSHA claim that the standard requires written documentation of MOCs. Which is exactly what OSHA does. What the standard doesn’t do is tell you how long to retain those MOCs.

m) Incident investigation – The standard requires a report (which means something in writing) and documentation of the resolution and corrective actions recommended in the report, and specifies that incident investigation reports be retained for 5 years. Nothing ambiguous here.

n) Emergency planning and response – The standard requires an emergency action plan in accordance with 29 CFR 1910.38, with the additional requirement of procedures for handling small spills. Interestingly, 1910.38 only requires written emergency action plans for facilities with 11 or more employees. If you are a PSM coordinator, your facility is probably large enough to require a written emergency action plan, but you don’t need to retain obsolete versions.

o) Compliance audits – The standard requires that you retain the two most recent compliance audit reports, each of which must be certified. Beyond the two most recent, compliance audit reports do not need to be kept on file.

So, the standard requires written documentation on almost all of the elements of PSM, but it only explicitly requires document retention on PHAs, incident investigations, and compliance audits. Why then did the past PSM coordinator leave such huge piles of documents in their PSM files?

Compliance Audits

On July 12, 2006, OSHA posted a standard letter of interpretation (updated on July 7, 2015) that addressed 10 issues, including the length of time to retain hot work permits (response 4).

In response 4, OSHA acknowledges that employers do not need to retain closed hot work permits. Then it adds, “However, to comply with [audit] provisions, an employer must audit the procedures and practices required by PSM and assure they are adequate and being followed…OSHA expects that employers would audit a statistically-valid number of hot work permits…One way to audit hot work permits is to evaluate compliance…is to complete the audit before the permits are discarded.”

So, just as is the case for hot work permits, many documents will need to be retained until a statistically valid number can be audited. That mean that documents without explicit retention requirements only need to have a statistically valid sample retained until an audit of those documents is complete. Since, audits should happen at a minimum of once every three years, that means documents need not be retained for more than three years, or until they are included in the audit pool, whichever comes first.

Management of Change Documentation

In that same standard letter of interpretation, OSHA addresses the length of time to retain MOC documentation . Their requirements for retaining MOC documentation are much broader.

For changes to chemicals or equipment, OSHA requires that the MOC documentation be retained for the life of the process as part of the process safety information.

For changes to procedures and practices, OSHA requires that the MOC documentation be retained until it is incorporated into the next PHA, which mean a maximum of five years.

For other MOCs, OSHA requires that MOC documentation be retained until it has been included in the audit pool, or three years, whichever comes first.

About Those PHAs That Must Be Kept for the Life of the Process

OSHA required that the first PHAs be completed by May 26, 1994. A lot has happened since then, which may include the loss of some early PHA documentation. What can be done? It is not as though a facility can go back and regenerate that documentation. Fortunately, OSHA presently has a reasonable approach to enforcement.

In OSHA’s CPL 03-00-021, PSM Covered Chemical Facilities National Emphasis Program, inspectors are directed to review the initial process hazard analysis and most recent updated/redo or revalidation. However, “any PHA performed after May 25, 1987 that meets the requirements may be claimed by the employer as the initial PHA for compliance purposes.” So, when you discover that your facility has not managed to retain every PHA it conducted over the life of the process, don’t sweat it. You just need two.

If You Didn’t Document It, It Didn’t Happen

The last reason for keeping documentation has nothing to do with safety. It’s about the inspection process. The number of things that must be done to comply with the PSM standard exceeds the number of things that standard requires be documented. During an inspection, however, the inspector will expect you to prove that you’ve done all the things you are required to do. The unofficial philosophy of OSHA inspectors is “If you didn’t document it, it didn’t happen.” So, even for those items for which the regulation does not explicitly require documentation, it becomes something we do defensively.

How far back? That’s a question for lawyers. Our advice is to consider your own compliance audits. Do you have evidence that you are complying with each of PSM’s requirements. Then you should be in good shape. Once you have newer evidence, you don’t need to keep the older evidence.

Perhaps the best thing you can do for the integrity of your PSM program is to discard documents that are no longer required. Do this in three steps:

- Retain the documents you are required by regulation to retain, and nothing older.

- Retain the most recent version of any document you are required to create, and nothing made obsolete by that most recent version.

- Retain examples of documentation that show you are doing the things you are required to do, even when the regulation expresses no explicit requirement for documentation. These should go back to your last compliance audit.

So, about those piles and piles of PSM documents: Must you be a hoarder? No. Get on with clearing out that crypt. You are a PSM coordinator, not a crypt keeper.