“What if this is as good as it gets?” — Jack Nicholson as Melvin Udall in As Good As It Gets, directed by James L. Brooks

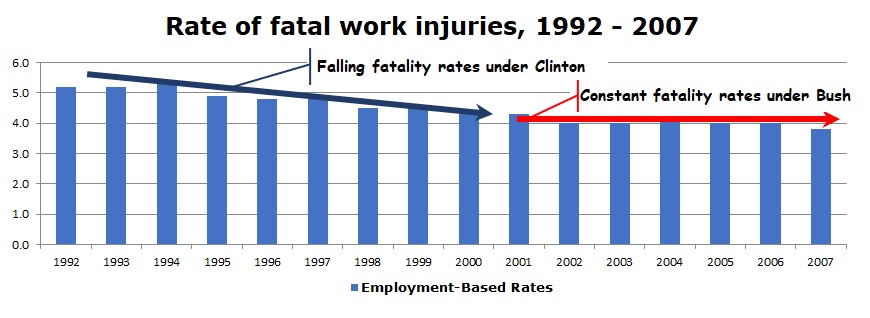

The year 2009 was first time I ever studied a graph of work-related fatality rates in the U.S. The data from the Bureau of Labor Statistics was available for the period beginning in 1992 through 2007. I was surprised to see how fatality rates seemed to correlate to administrations. Was it possible that the carrot approach of making recommendations was not as effective as the stick approach of issuing citations and levying fines?

Annual fatality rates reported by the Bureau of Labor Statistics, 1992 – 2007

Carrots and Sticks

The irony is that the average annual amount of OSHA fines was not much different between the Clinton administration and the Bush administration. For that matter, neither were the average OSHA budgets. The carrots and the sticks were about the same.

It’s hard to let go of a simple explanation, though.

At the time, critics complained about lax enforcement of OSHA regulations during the Clinton administration, despite a consistent downward trend in the fatality rate during that administration. It probably goes without saying that critics complained about the enforcement of OSHA regulations during the Bush administration.

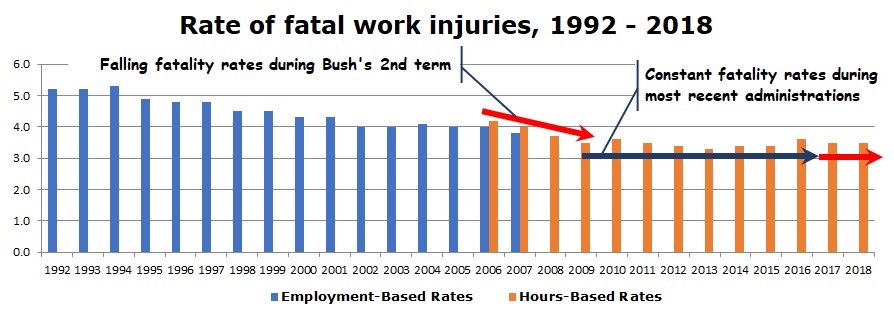

Even as the critics complained, however, fatality rates in the U.S. workplace began to fall again. The second term of George W. Bush’s administration, during a period of falling OSHA budgets, saw an overall rate of decline sharper than anything during the previous administration.

Then, during the Obama administration, OSHA’s budget increased and the annual amount of OSHA fines increased. Yet fatality rates in the U.S. workplace remained statistically constant throughout the Obama administration and continued to stay constant into the Trump administration.

Annual fatality rates reported by the Bureau of Labor Statistics, 1992 – 2018

Maybe, just maybe, fines and budgets aren’t as related to workplace safety as we’ve been led to believe. Maybe a workplace fatality rate of 3.5± fatalities per 200,000,000 hours worked is just as well as can be done in a developed industrial nation like the United States. Maybe this is as good as it can get.

Is This As Good As It Gets?

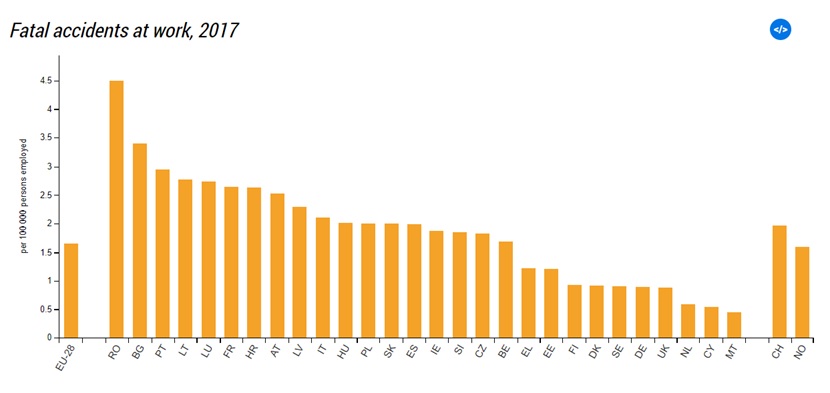

As a matter of fact, it can be better. The European Union had an overall workplace fatality rate of 1.65 fatalities per 100,000 workers in 2017. (At 2,000 hours per work year, 100,000 workers are approximately the same as 200 million hours worked). That is half the workplace fatality rate in the U.S. On a country-by-country basis, every country in the European Union except Romania did better than the U.S. The workplace fatality rate in Malta was only 0.45 fatalities per 100,000 workers.

Annual fatality rates compiled by Eurostat for the EU-28, Switzerland and Norway

Even considering only the European members of the G7 – France at 2.6, Italy at 2.1, Germany at 0.9, and the United Kingdom at 0.9 – it becomes obvious that the fatality rate in the United States hasn’t plateaued because we’ve reached the natural limit of progress.

A fatality rate of 3.5 fatalities per 100,000 full-time equivalents is not as good as it can get.

Is this simply as good as we want to get?

Know-How Isn’t Enough

In order to improve safety, we have to know how to be safer. But it is not enough to know how. We must also want to be safer.

Consider the COVID-19 pandemic. We know how to stop the spread of this deadly disease: Wear a mask. Wash hands frequently. Social distance. Self-quarantine when showing any symptoms. And at a societal level, test, trace, and track.

But we don’t and the number of cases has exploded. It’s not because we don’t know what to do, but because we don’t want to do it. At some level, as a society, we’re content with things as they are. Just as we seem to be content with a workplace fatality rate of 3.5 fatalities per 100,000 full-time equivalents (FTEs).

Perhaps we should not be surprised that the EU, which has driven its workplace fatality rate down to less than half of that in the U.S., has also driven back the COVID-19 pandemic.

Not Sufficient, But Necessary

Because of the Law of Conservation of Recklessness, I am increasingly convinced that there is little that I can do as a safety professional to make people safer if they are already as safe as they want to be. And I don’t know how to make people want to be safer. As a safety professional, though, I can show people how to be safer.

In 1970, when OSHA first came into being, the fatality rate was around 20 fatalities per 100,000 FTEs. By 1992, it had fallen to 5 and during the eight years of the Clinton administration, it fell to 4. In the course of just the second term of the Bush administration, it fell again, to 3.5. The rate can fall, when the desire is there.

Our job, then, is to make sure that the know-how is there once the desire is there. The rate has fallen, in part, because the desire to be safer is there. But it couldn’t have happened if we had not all been out there, showing our colleagues the way. So, keep it up. We’ll get there. I don’t know why, and I don’t know when, but we’ll get there.

Safety professionals and psychologists can only take us so far. Perhaps it’s time to look to philosophy and philosophical reasoning?

[…] Since then, we’ve flat-lined, stuck at around 3.5 fatalities per 100,000 FTEs. It’s almost as though this is a good as we are capable of. It’s not, though. Almost all our European neighbors do better. The UK, for instance, is four times safer. […]