“I did then what I knew how to do. Now that I know better, I do better.” — Maya Angelou

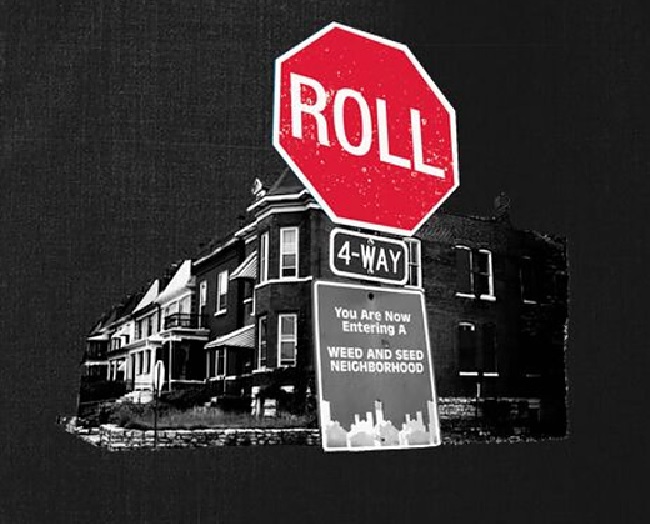

Many St. Louis drivers view stop signs as suggestions; they don’t see a full stop is either required or expected. And this isn’t just young hooligans in muscle cars. It includes little old ladies in Volvos, parents driving a minivan full of kids, school bus drivers, and, yes, police.

It’s not because St. Louis drivers don’t know better. When asked if drivers would be safer if they came to full stop at a stop sign, instead of rolling through, every St. Louisan I’ve ever asked has always agreed: “Yes, coming to a full stop is safer.” Yet they don’t.

It Matters

They are correct about stopping at stop signs being safer. St. Louis, Missouri is one of the most car accident-prone cities in the United States, second only to Columbus, Ohio. So why do St. Louis drivers choose to drive in a way that makes them—and others—less safe? I don’t think it is nihilism. St. Louis drivers don’t hurtle through stop signs because they believe that lives don’t matter. The people of St. Louis cling to life just as fiercely as people everywhere.

I believe the relationship that St. Louis drivers have with stop signs is based in large part on growing up in an environment where that it just how it is done. It doesn’t help any that they have lots and lots of experience—from the time they were young children—of rolling through or flying through stop signs with no ill effect. The only effect was that they got to where they were going quicker. If rolling through a stop sign has nothing but upside, why stop? Sure, they might get a ticket, but convinced that tickets are really just for raising revenue for the city, it is easy to conclude that if not a ticket for this, then a ticket for something else, concluding “If you are going to do the time, then might as well do the crime.”

Process Safety Management

I’ve never been shy about making the distinction between Process Safety Management (upper-case PSM) and managing process safety (lower-case psm). The first we do because it is required by our government. The second we do because we want to be safer. In an ideal world, they are the same things.

It is not an ideal world.

When an organization decides to ignore elements of PSM, or simply neglects to comply with elements of PSM, they are making a business decision that the chances of being inspected and costs of being cited are low enough that it is not worth the certain cost of compliance. A business decision. It is not a decision I will ever encourage, but it is not my decision to make.

When an organization decides to ignore elements of psm because it increases the cost of production or delays new product introduction, they are making safety decision that puts the lives of workers’ and members of the community at jeopardy. They are making a trade-off where the benefit accrues to the organization, while the cost accrues to the workers and community that no longer have that protection.

I have never worked with an organization that was indifferent to the lives of their workers or the community. Even organizations with the most fraught labor relations do not want to see their workers hurt or killed on the job.

The challenge for safety professionals, then, is to convince their organization that things being done for safety is something they want to do, to avoid injuries and save lives, not simply to comply with regulations, for which the fines for non-compliance are insufficient to be persuasive.

The Real Challenge

The biggest challenge is that rarely does doing things less safely than they should be done result in immediate and certain death. If it did, the work of safety professionals would be much, much easier. All we would have to do is determine the safe way to do things, explain it to others, and our work would be done. However, the odds favor doing things unsafely, at least on a case-by-case basis. “We’ve been doing it this way for years, and nothing has ever gone wrong.”

It’s like running a stop sign. The organization might get away with it. In fact, probably will get away with it. But the organization doesn’t know it’s gotten away with it until it’s actually gotten away with it. Get away with it, and the organization looks like it’s run by geniuses who take calculated risks that pan out. Don’t get away with it and have an incident, perhaps a fatality, then the organization is run by a bunch of greedy, money-hungry demons who are willing to sacrifice workers’ lives in the name of profit. Just ask any reporter.

Understanding the Upside

When faced with a choice between one course of action and a safer course of action, why would anyone choose the more reckless course of action? Because they understand the upside of that course of action, and without fail, the upside is immediate. The safer course of action almost always comes at a higher cost and the benefit is delayed or goes to someone else.

Safety professionals will often point out the potential negative impacts of more reckless choices without ever addressing the likelihood of those negative impacts or the upside of the more reckless choice. People then make their cost-benefit decisions about safety based on their unchallenged impressions about the benefit of the reckless course of action and the difference in costs, but with only a vague idea about the benefit of the safer course of action.

So, they take a “calculated risk” without ever doing any calculations.

The Job of Safety Professionals

For the most part, safety professionals serve as advisors. Our job is to know how to operate safely and to make sure that everyone else knows how as well. The decision to operate safely falls to others, and usually, we are powerless to compel anyone to be safer than they want to be.

It falls to us, then, to not only know how to operate safely, but to understand why people and organizations choose to operate more recklessly than we advise. Then, with that understanding, make the case. If we can’t make the case, perhaps we’re asking for too much.