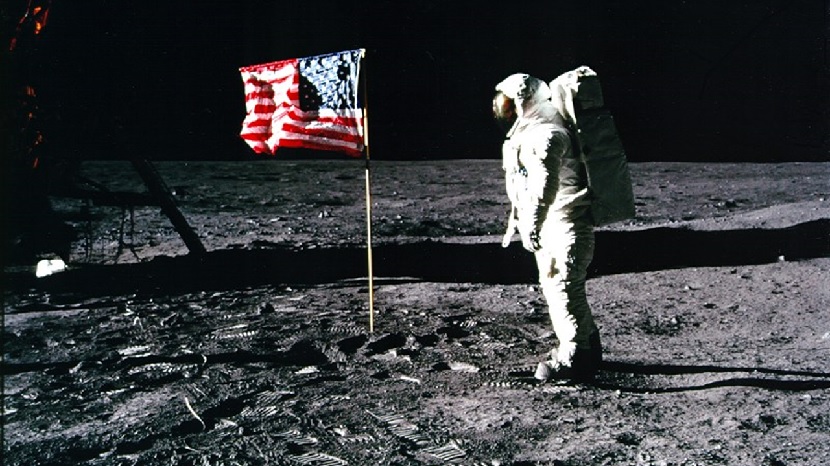

“If we can put a man on the moon, why can’t we…” — Nearly Everyone

Fifty years ago, humans first walked on the moon. It was and remains a remarkable and courageous feat of technology and determination. Having achieved it, though, most of society lost interest and moved on. Humans haven’t been back on the moon since 1972.

Unlike a moon landing, process safety is not a goal to achieve and then lose interest. “If we can go a week without a catastrophic release of hazardous materials, why can’t we…” Process safety is a way of looking at the world, a way of approaching the chemical enterprise. It is not something that is ever finished and not something in which we can lose interest.

July 20, 1969

I remember the first moon landing. I had just turned 11, so I was convinced that there was special significance to the mission being the Apollo 11. It was a Sunday night and my dad had to leave for work early the next morning, but my parents let my brothers and sister and I stay up late to watch Neil Armstrong, then Buzz Aldrin, step onto the moon. In fact, they insisted we stay up late to watch. We crowded together in my parent’s bedroom to watch the family television—a Quasar color television of which my father was very proud and very protective. As Neil Armstrong readied to jump off the ladder onto the surface of the moon, I remember how quiet we all were, the only sound being the voices from the television.

If you are too young to have watched the first moon landing, it’s on YouTube. The video is three hours long, but Neil Armstrong’s historic comment, “That’s one small step for man, one giant leap for mankind,” is very early—just a little more than three minutes into the video.

It never occurred to me that the mission would not be successful. To an eleven-year-old who had grown up with the U.S. space program as a constant, the moon landing seemed…inevitable.

Dates to Remember

Thanks to the space program, I grew up believing in the inevitability, the invincibility of technology. Even the Apollo 13 near-disaster in April 1970 didn’t challenge my confidence in technology. Jack Swigert’s now famous comment, “Houston, we’ve had a problem,” and NASA’s response only served to reinforce my confidence in the ability of engineers to solve any problem, to overcome any obstacle.

It took the Space Shuttle Challenger explosion, on January 28, 1986, so close on the heels of the Bhopal chemical disaster on December 3, 1984 to finally shake my faith in technology. Engineering is a compromise between schedule, performance, and cost, so nothing is perfect. Things fail. Entropy, that bastard, is always working against us. There is nothing inevitable about technology, and there is nothing inevitable about safety. Process safety requires our constant attention.

There are a series of dates that help me to remember:

- June 1, 1974 –Nypro disaster, Flixborough, England

- December 3, 1984 – Union Carbide disaster, Bhopal, India

- July 6, 1988 – Piper Alpha disaster, North Sea

- October 23, 1989 – Phillips disaster, Pasadena, Texas

- March 23, 2005 – BP Refinery explosion, Texas City, Texas

- September 10, 2010 – Deepwater Horizon disaster, Gulf of Mexico

- July 6, 2013 – MM&A train derailment, Lac-Mégantic, Quebec

- August 13, 2015 – Ruihai Logistics warehouse explosion, Tianjin, China

These are the dates and disasters that keep my attention focused. I’m sure others have their own lists. When considering this list, I notice a series of events that occurred shortly after I began my career in the 1970s and profoundly influenced the direction of my career. Then there is a gap of almost a generation before there is another series of events. It’s almost as though we have to learn the lessons all over again.

Recent Chemical Accidents

The Center for Chemical Process Safety keeps track of chemical accidents in the news. During a recent four-month stretch, there were 51, averaging about one every other day. The news accounts were of events ranging in severity from a spill of Coca-Cola that flooded a Texas neighborhood to a plant explosion in Wisconsin with two fatalities.

“We put a man on the moon. Why can’t we keep chemical disasters from happening?” We can. We do. Every day, thousands of chemical plants operate around the world without a disaster. Then there’s tomorrow.

We are not done. The moment we believe we are done is the moment we will be reminded that we need to start over.

One Small Step

Unlike the moon landing on July 20, 1969, there will never be a date that can be commemorated with a 50th anniversary celebration of when process safety was achieved. When it comes to process safety, the only dates we will ever commemorate will be the dates of disasters, and it will be with memorials, not celebrations.

Process safety is not a destination, but a journey. Like the moon landing, process safety can include “one small step”. But then it needs to include another. And then another. Then another. Those steps add up to a journey. We’ll never get “there”, but we can always move in that direction. The only other choice is to give another generation another set of dates to memorialize.