“If you don’t get better, staying the same is probably not good enough.” — Chris Mullen

If a bowler always—always—bowls a perfect 300, they are as good as a bowler can be. If other bowlers also develop that level of skill, they cannot beat a perfect 300. The best they can do is tie. There is no getting better.

Usually, though, that’s not how it is. A baseball pitcher who routinely and regularly throws a perfect game will eventually face a batter who can best him. The world record for women’s pole vaulting is 5.06 m, set on 28-May-2009. However, there have been longer stretches between new world records since the first world record was set on 14-May-1910 (at a now unimpressive 1.44 m). Eventually, someone will set a new record.

How high is high enough? Pole vaulting is conducted at field and track meets, the Olympics being the grandest of them all. To win, a woman does not need to set a new world record, as the last three summer Olympics have shown. She needs to vault higher than all the other pole vaulters at the meet.

Continuous Improvement

Most of us accept the premise that we must continuously improve and that if we don’t, then for all practical purposes, we’re getting worse. There is no perfect (bowling notwithstanding), so we can always get better. In safety, perfect would mean that no one suffers a work-related fatality, injury, or illness. Ever. Never mind whether that is possible. Is it a worthy goal?

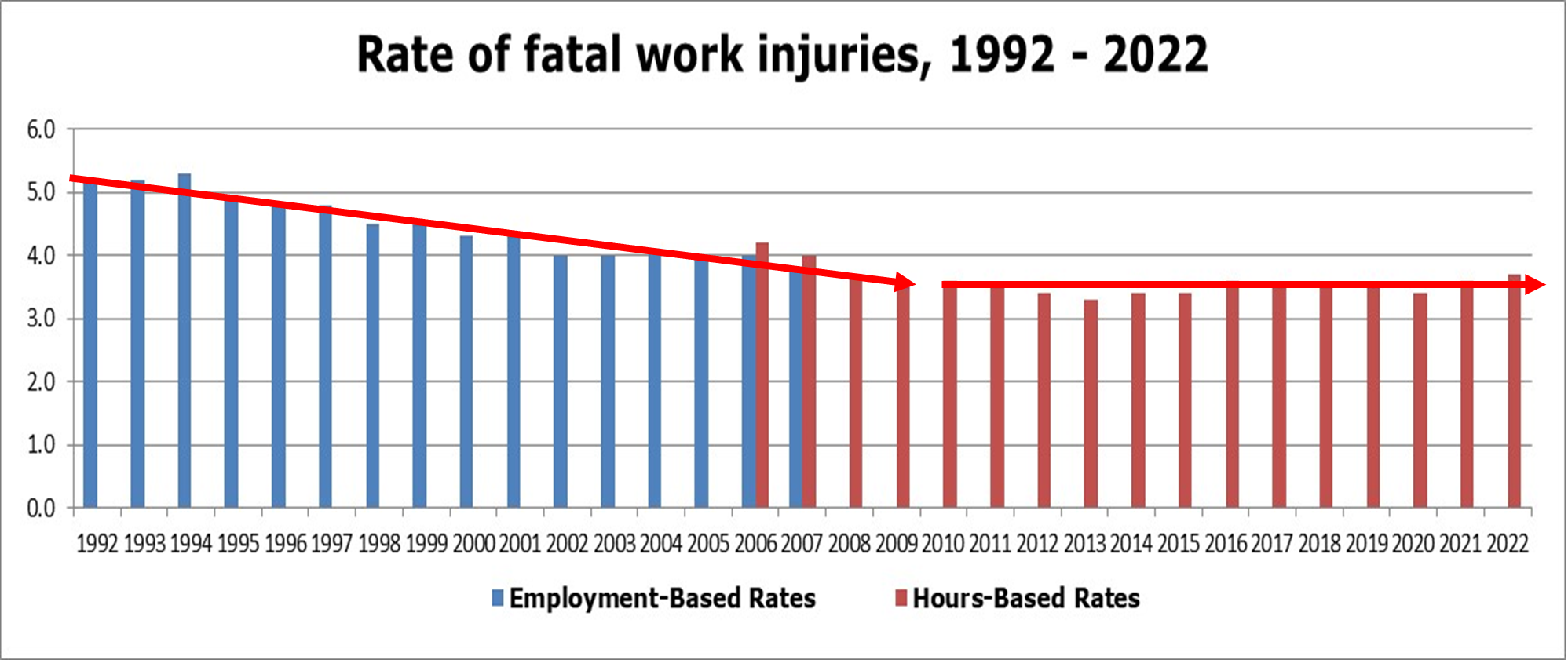

A few years ago, I explored the question of whether workplace safety was already as good as it could get. Looking at data through 2018, I noted that the work-related fatality rate in the U.S. had been level at 3.5± fatalities per 100,000 full time equivalents (FTEs) since 2009.

Annual work-related fatality rates reported by the Bureau of Labor Statistics, 1992-2022

Annual work-related fatality rates reported by the Bureau of Labor Statistics, 1992-2022

Four more years of data shows that we are still stuck at 3.5± fatalities per 100,000 FTEs. That same piece also pointed out that the European Union had an overall work-related fatality rate of 1.65 fatalities per 100,000 FTEs, with every country but Romania better than the U.S., and Malta at a work-related fatality rate of 0.45 fatalities per 100,000 FTEs. It was, and remains, possible to do better.

Not All Fatalities Are Work-Related

Every safety professional I know is involved primarily in workplace safety. Perhaps that is why I tend to focus so much on work-related fatality rates. However, work-related fatalities do not account for many of the fatalities that we experience as a society. Before the Covid-19 pandemic, which caused a significant jump in the overall fatality rate in every country and region of the world, the crude fatality rate in the U.S. averaged around 850 per 100,000 people. It was 870 per 100,000 people in 2019.

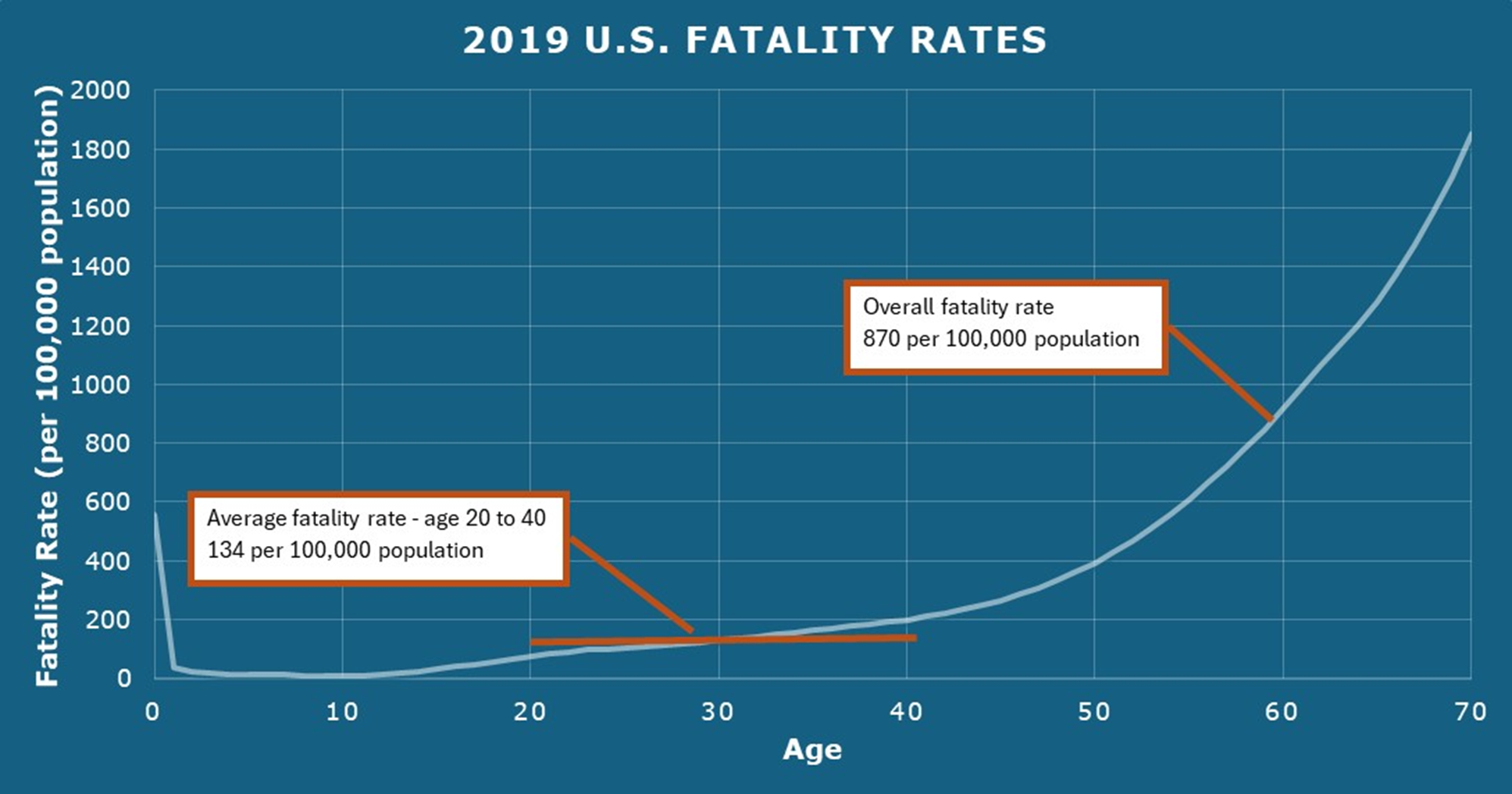

However, it’s not reasonable to compare the U.S. work-related fatality rate of 3.5± fatalities per 100,000 FTEs to the overall fatality rate of 870 per 100,000 people, especially since most of those fatalities occur in a population that has aged out of the workforce. A better comparison would be to the fatality rate of the population that hasn’t entered the “wear-out” period of the bathtub curve, which starts at about age 40.

Fatality rates calculated from Social Security Administration actuarial life tables.

Fatality rates calculated from Social Security Administration actuarial life tables.

The average fatality rate for people between the ages of 20 and 40 years old was 134 fatalities per 100,000 population in 2019, the most recent non-pandemic year for which the Social Security Administration has published data.

If the fatality rate in the workplace had been the same as the fatality rate for life in general (based on 40-hour workweeks), the work-related fatality rate in the U.S. in 2019 would have been

134 fatalities/100,000 people x 1 person/FTE x 40 work-hr/week x 1 week/168 hr

= 32 fatalities per 100,000 FTEs

In other words, work in the U.S. overall is about ten times safer than life in general.

How Safe Should Work Be?

Everyone I’ve ever spoken to feels that work should be safer than life in general. In 1970 the work-related fatality rate was around 20 fatalities per 100,000 FTEs, not much lower than the adjusted overall fatality rate. Still, U.S. society felt it was too high, prompting the creation of the Occupational Safety and Health Administration.

Now the work-related fatality rate is about ten times lower than the adjusted overall fatality rate of life in general. Is that low enough? The member countries of the European Union don’t believe so, or they wouldn’t have driven their rates down so much further. Are they satisfied with a work-related fatality rate of 1.65 fatalities per 100,000 FTEs? Probably not, or they wouldn’t continue to pass new safety regulations, and instead would focus on maintaining enforcement of the safety regulations already in place.

The safest occupations in the U.S. are librarian and mathematician, with work-related fatality rates of around 0.2 to 0.4 fatalities per 100,000 FTEs, depending on the year. If the overall work-related fatality rate were around 0.2 to 0.4 fatalities per 100,000 FTEs, would that be low enough? Or would we want to improve another order magnitude after achieving that? And then another?

How Low Is Low Enough?

For many, the need for continuous improvement is an article of faith. Safety is unlike pole vaulting, where there is always higher. No, safety is like bowling, where there is a “perfect”. But is that a worthy objective, especially in a world of finite resources and competing priorities? Perhaps there is an objective short of zero that is low enough. Unless we discuss it, however, will we know what it is when we reach it? Have we already reached it and that’s why improvement seems to have stopped? I don’t think so, but regardless of what I think, it’s time for a new conversation about work-place safety. How low is low enough?