“It’s often said that the definition of insanity is doing the same thing over and over and expecting a different result. Very, very, very often said.” – Daniel D’Addorio

The end of one year and the beginning of a new year is often a time of reflection and planning. Reflection on what we did right and what we did wrong. What went well and what went badly. And then making plans for improvement in the coming year.

Admittedly, our reality often fails to live up to our plans. But as Dwight Eisenhower said when he quoted an old military adage, “Plans are worthless, but planning is everything.”

For those of use concerned about workplace safety (which should be everyone who works, and everyone who loves someone who works), questions we should be asking ourselves are, “Are we on the right track and satisfied with the direction we’re heading, so we should keep on keepin’ on? Or should we be trying to change the way we work so we can move in a better direction?”

Predictions for the Latest BLS Data

A few weeks ago, in anticipation of the Bureau of Labor Statistic releasing the injury, illness, and fatality data for the U.S. workplace in 2021, we made some sad predictions. Despite our hope for post-pandemic improvements, we stated that “we expect that the overall work-related fatality rate will still be around 3.5 fatalities per 100,000 full time equivalents, unchanged for more than a decade. We expect that the occupations with the highest fatality rates will still include commercial fishing, logging, roofing, and trash collection.”

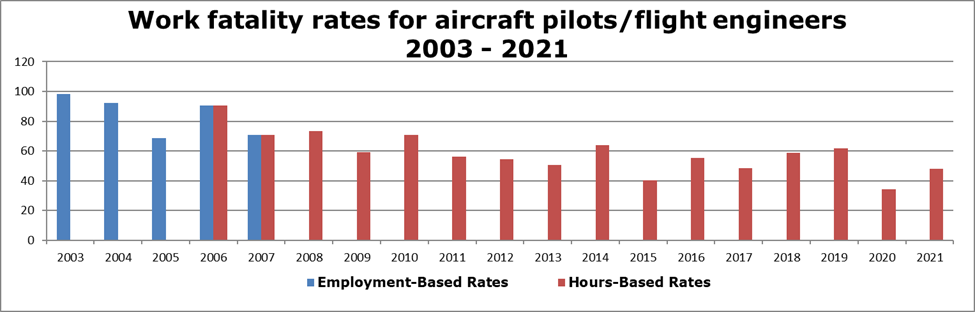

But we pointed to a bright spot in the data from the previous year, noting that “for years, aircraft pilot/flight engineer has also been consistently in the top five list of occupations with the highest fatality rates, ranging from 49 to 64 fatalities per 100,000 full-time equivalents. Then, in 2020, the fatality rate for that occupation dropped to 34 fatalities per 100,000 full-time equivalents…The most interesting thing that we will see in the upcoming BLS report is how aircraft pilots and flight engineers did in 2021. If it stays low, then we can have even greater hope that we can make significant changes elsewhere.”

Overall, How’d We Do?

So, how did the U.S. workplace do in 2021, the year the Covid-19 vaccine became readily available to those who wanted it and the year we began returning to work after being in quarantine for almost a year?

The number of work-related fatalities climbed back toward pre-Covid levels. There were 5,190 work-related fatalities in 2021, compared to 4,764 in 2020 and 5,333 in 2019. However, the overall fatality rate remained steady. As the number of workers increased, the number of fatalities also increased. The rate in 2021 was 3.6 fatalities per 100,000 full time equivalents (FTEs), compared to 3.4 fatalities per 100,000 FTEs in 2020 and 3.5 fatalities per 100,000 FTEs in 2019. In fact, since 2009 the work-related fatality rate has ranged between 3.3 and 3.6, with an average of 3.48 and standard deviation of 0.09. There was a moment when the 2020 data suggested that one silver lining of the Covid-19 pandemic was the beginning of a new downward trend. Alas, it appears that 2021 is proving the cynics who thought things are no different than the past decade were right. If this were a control chart, a production engineer would conclude that the process was in statistical process control. The year 2021 was no better and no worse than the U.S. workplace is capable of or has been capable of since 2009.

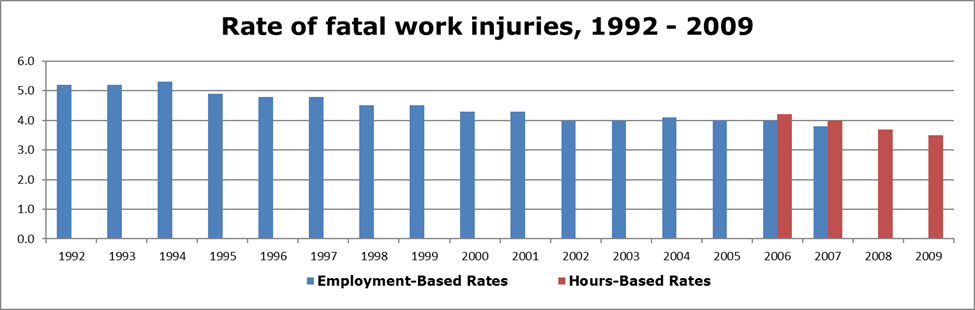

Compare this very stable period with the preceding 17 years. While the fatality rate during 2009-2021 fluctuated around 3.48 (going up in four years, down in five years, and staying the same in three years), the fatality rate fell consistently from 1992 to 2009 (going down in nine years, staying the same in six years, and only going up in two years). And the difference is not due to the BLS switching from the number of workers to the number of FTEs as the basis for their calculations.

See! We have been through a period where employers and their workers managed to drive down the work-related fatality rate for almost two decades.

What About Those Dangerous Occupations?

Since 1992, the first year for which data is readily available, the two most fatal occupations in the U.S. have been logging and commercial fishing. The year 2021 proved to be no different. Roofers have the third most fatal occupation. Trash collecting is still one the most fatal occupations. Every occupation in the list of the ten most fatal has been there before.

But there was that bright spot. In 2020, the work-related fatality rate for aircraft pilots/flight engineers fell to the lowest point it had been since BLS began reporting it. Looking at the five-year period leading to that low point (2016 – 2020), it appeared to be statistically lower.

But the rate has gone back up. In 2021, the rate was back up to 48 fatalities per 100,000 FTEs. Looking back to 2003 and including 2021, it becomes apparent that 2020 was simply one more year in a bumpy downward trend in the fatality rates for aircraft pilots/flight engineers. Bumpy, but consistently downward. Good for them!

How Have We Done in Chemical Manufacturing?

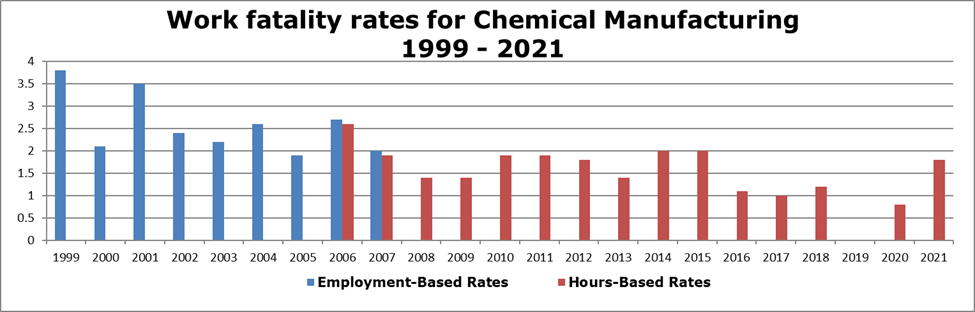

Which brings us to our own industry. The BLS specifically reports data for chemical manufacturing back to 1999. Like the U.S. workplace as a whole, the fatality rate fell, albeit unevenly, until 2009. Then it began to hold at around 1.5 fatalities, with a standard deviation of 0.4. Yes, still in statistical process control, but with a much bigger relative standard deviation.

The fatality rate in 2020, the year of Covid, was 0.8 fatalities per 100,000 FTEs, the lowest it has been in any year reported by the BLS. It would be nice if that had been a harbinger of improvements to come. Disappointingly, the fatality rate in 2021 was back up to 1.8 fatalities per 100,000 FTEs, suggesting that things are the same as they always were. Happily, chemical manufacturing has always proven to be safer than the overall U.S. workplace and continues to.

Worse Than Last Year, About the Same As Before

In general, the work-related fatality rates in 2020, the year of Covid-19, were noticeably lower than typical. Sure, the number of work-related fatalities were less, which we would expect with the noticeably smaller workforce. But even the rates improved some. That suggests that when things are robust, we operate closer to the edge, but when the economy shrinks but not the infrastructure, we have more margin for error. That margin, though, is slender. (On the other hand, the data can also be used to support the argument that any differences in 2020 were not statistically significant.)

In any case, it is clear that 2021 was a year of returning to the “old normal” in terms of workplace safety.

Don’t Be Insane

It would be insane to suggest that the way to improve workplace safety is to have another pandemic. In 2020, the total number of workplace fatalities fell by 569. Then, in 2021, the total climbed by 426. However, the total number of deaths in the United States due Covid-19, so far, is over 1.1 million. That is not a trade-off anyone would want to make.

We must continue doing what we’re doing, or workplace safety will get worse. However, if we only continue doing what we’re doing, workplace safety will not get better. We’ve got to find a way to move to a new paradigm. It’s the only sane thing to do. As you consider your new year’s resolutions, don’t just think about ways to do your work better and safer. Think about ways the work can be done differently.