“Where our memories fade, the Internet never forgets. At the drop of a hat, friends, family members, acquaintances, and even strangers can call up these records, and worse, they can use them against us.” — May Crockett

Nextdoor, the “hyperlocal social networking service for neighborhoods” has been abuzz in my neighborhood for the past few days. Someone complained about the “chemical stench” coming from across the river, and in less time than it takes for a conspiracy theory to spread around the world, dozens of my neighbors had moved beyond speculating about the source to blaming any one of the chemical plants that are a couple of miles away, on the other side of the Mississippi River.

As for me, I could smell something. It was the stench that comes from the combination storm and sanitary sewers in the old parts of our city, especially in the summer after several days without rain.

In the meantime, my neighbors have dredged up every negative report or speculation associated with any of those plants and posted links to them.

The Internet never forgets.

The Internet Never Forgets. Really?

Stephan Dreyer wrote a blog that tackled the question of whether the Internet, like a diamond, is forever. Basically, he concluded that most online content will be gone sooner or later because of “URL rot” or “link rot”. Unfortunately, however, none of us get to determine which content fades away, and which lingers. And the more we try to make it go away, the more likely it is to stick around—the Streisand Effect, a social phenomenon that occurs when an attempt to hide, remove, or censor information has the unintended consequence of further publicizing that information, often via the Internet.

So, if we have a problem at our plant, that information will still be there on the Internet for our neighbors to find and post on Nextdoor the next time we have a problem, great or small. The Internet may forget those pictures of that party you attended in college, but it won’t forget your plant.

The Benefit of the Doubt

Every plant needs licenses and permits to operate. In addition to those issued by various governments—federal, state, and local—each plant also needs the permission of its community to operate. A community determined to put a plant out of operation will succeed. And nothing makes a community more determined to put a plant out of operation than being a bad neighbor.

Being a good neighbor means not imposing on the community. Not having problems goes a long way, but it is not enough. A good neighbor is also one the community trusts, and it is to trust a neighbor that is known. So, community relations are important, not just as an exercise in managing public image, but in making sure that your community knows you. That way, when problems inevitably occur (which they will regardless of even the most relentless drive toward zero incidents), the community will give the plant the benefit of the doubt.

In the absence of that trust, the community will assume the worst. And share it on social media, because it is always easier to get people to assume the worst.

Keep the Community Informed

As much as we love to share good news, good news doesn’t get anywhere near the same attention as bad news. So, we have to work hard to share good news and to keep open the channels for sharing that news.

More importantly, though, we need to share our bad news. In the absence of that sharing, there will always be individuals ready to step in and fill the gap. They’ll fill the gap with alarmist speculations, conspiracy theories, and worst of all, our past problems. And it will be the last that will be hardest to dismiss.

Fortunately, the same social media outlets that serve our detractors can serve our plants. When something goes wrong, share it with the neighbors. If Nextdoor can circulate speculation about what is going on at your plant, then Nextdoor can also circulate information about what is really going on at your plant. Generally, people understand and forgive honest mistakes—mistakes that are acknowledged and learned from. It is in the denial of those mistakes, or their significance, or an outright coverup that causes the real condemnation.

If the plant is doing something that it simply refuses to admit to, then that is a different issue and perhaps it deserves the condemnation it gets.

Moving Beyond CAPs

In the early years of Responsible Care, large chemical companies fell all over themselves to establish Community Advisory Panels. They are still around, but don’t get much attention anymore. Perhaps that is for the best. According to Gwen Ottinger (in a post entitled Community Adjourned: Assessing Community Advisory Panels), they had four goals:

- Building trusting relationships between chemical facilities and community members

2. Educating community members about plant operations and performance

3. Informing facilities about community concerns

4. Facilitating environmental improvements at chemical plants

The CAPs did a pretty good job at meeting the first two goals; not so well at the last two. Additionally, critics often dismissed CAPs as merely public-relations exercises. Well, its two decades later, and now there is social media. Instead of working through community leaders, it may be time to reach out directly to the community.

Reach Out

Social media is here. For many, it is the only place they get news. It’s easy to use, and gives your plant a better chance at explaining what is actually going on. The traditional media will show up with camera and microphones, and if you are lucky, almost a quarter of what they report will be correct. If they don’t show up, then your neighbors will be left to speculate, and that is never good.

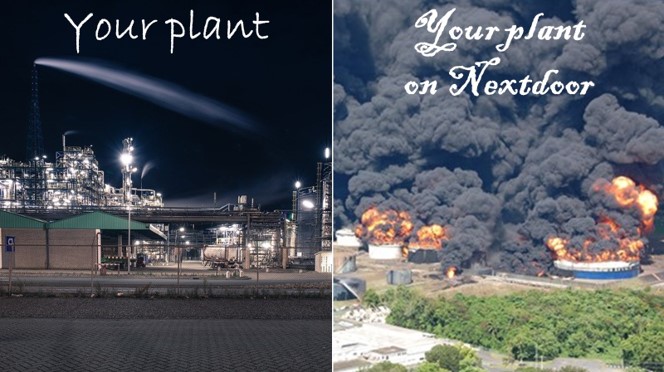

Avoid the speculation. Get into the habit of letting your neighbors know what is going on, and they can help pass the word along. Then, when you really need for them to get the story right, you’ll have a chance. Perhaps then we can change the meme so the photo for “Your plant on Nextdoor.” is the same as the photo for “Your plant.”