“The more things change, the more they are the same.” Alphonse Karr

Recently released fatal injury data from the Bureau of Labor Statistics (BLS) shows that self-employed workers are almost five times as likely to die on the job as employees.

It Seems Like Nothing Much Has Changed

As promised, the BLS released its 2015 census of fatal injuries in the workplace on Friday, December 16, 2016. While the news release and the chart package that typically accompanies it go on for several pages, at first glance, it appears that the news is that overall, nothing much has changed.

When the economy tanked in 2008, the total number of workplace fatalities fell from over 5,200 in 2008 to around 4,500 in 2009. As the economy recovered during the last seven years, the number of workplace fatalities each year has generally inched upward, with a total of 4,836 in 2015. The annual number of workplace fatalities has still not reached pre-recession levels.

The increase in workplace fatalities has almost kept pace with growth in jobs, so that the workplace fatality rate has been pretty flat, perhaps showing a slender downward trend. The workplace fatality rate has averaged slightly more than 3.4 fatalities per 100,000 full-time equivalents since the beginning of the great recession. In 2015, the rate was 3.38 fatalities/100K FTE, a value slightly less than the average for the last seven years, but without statistical significance.

Workplace Safety in the Gig Economy

One of the more interesting statistics in the report is the fatality rate of the self-employed compared to the fatality rate of the employed. Overall, the fatality rate for workers in the U.S. is 3.4 fatalities/100K FTE. This means that of 100,000 U.S. workers selected at random on January 1, we could expect that 3 or 4 of them died on the job during the following year. For employees—workers that are on someone else’s payroll—the fatality rate is 2.8 fatalities/100K FTE. The self-employed, who are neither protected by OSHA nor compelled to comply with OSHA regulations, have a fatality rate of 13.1 fatalities/100K FTE.

This may be a glimpse into the effect that the growing gig economy is going to have on workplace safety.

On the other hand, it may simply be a reflection of how safe we want to be when left to our own devices.

OSHA citations frequently vilify employers for putting profits ahead of worker safety. But when the worker and the employer are one and the same, that balance between profits and worker safety is typically free of any ethical or moral quandary. The risks and the benefits accrue to the same person. Is it possible that a fatality rate of 13.1 fatalities/100K FTE represents what society is actually prepared to tolerate? Or is it that the self-employed are just natural risk-takers and this is just a manifestation of their willingness to take more risks than society as a whole? In either case, a further shift to a gig economy of self-employed people is likely to result in a generally more dangerous workplace.

How We Die on the Job

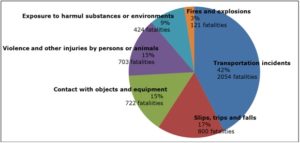

The BLS characterizes injuries on the job, fatal and non-fatal, according to seven types of events. One, overexertion, is never listed as a cause for fatal injuries. The other six are each causes for fatal injuries, year after year. And year after year, they rank about the same, with about the same contribution as a percentage of the total.

Fatalities in the US Workplace – 2015

Once again, transportation incidents are the leading cause of death on the job, accounting for around 40% of the total number of workplace fatalities. Once again, the next three categories—slips, trips, and falls; contact with objects; and workplace violence—each accounting for 15% ~ 20% of the total number of workplace fatalities. And once again, the causes of workplace fatalities that can be attributed to process safety—harmful exposures and fires/explosions—account for a little over 10% of workplace fatalities, with fatal exposures outnumbering fire and explosion fatalities by about 3 to 1.

When considering the six types of events, it is important to keep in mind that what we typically think of as transportation incidents—roadway traffic accidents—are the cause of only 60% of transportation incident fatalities. Likewise, slips, trips, and falls at the same level account for 20% of fatalities caused by slips, trips, and falls, and that homicides account for 60% of fatalities resulting from workplace violence, with workplace suicides and attacks by animals accounting for the others.

Murdered on the Job

Men are far more likely than women to die at work as a result of contact with objects and equipment: 16% of workplace fatalities of men compared to 6% of workplace fatalities of women. On the other hand, women are far more likely than men to be murdered on the job; 18% of workplace of fatalities of women are homicides, compared to 8% of fatalities of men. Process safety concerns are equal-opportunity killers. Twelve percent of fatalities are the result of exposure to harmful substances or environments, or to fires and explosions, for both men and women.

The Most Dangerous Jobs

The list of most dangerous occupations is the about the same for 2015 as it is for earlier years:

- 133 fatalities/100K FTE Loggers

- 55 fatalities/100K FTE Commercial fishers

- 40 fatalities/100K FTE Aircraft pilots and flight engineers

- 40 fatalities/100K FTE Roofers

- 39 fatalities/100K FTE Trash collectors

- 30 fatalities/100K FTE Structural iron and steel workers

There are no surprises here, but if you’ve not seen this list before, some explanation may be in order. Loggers and commercial fishers should come as no surprise. Their jobs are so dangerous, they’ve had their own reality TV shows. Likewise, while not exotic enough to get reality TV shows, most people aren’t going to be surprised to learn that roofers and structural iron workers often fall to their deaths, especially when they aren’t provided with adequate fall protection.

But pilots and flight engineers? Isn’t commercial aviation supposed to be the safest way to travel? It is, but most pilots and flight engineers don’t work for the airlines. They are cropdusters, bush pilots, traffic helicopter pilots. These are dangerous jobs. As for trash collectors, think of any other job where someone is expected to work in traffic. For trash collectors, there are no cones, no warning of “SLOW” or “Worker ahead”. They’re just there, and they are working directly with equipment that is specifically designed to crush organic matter.

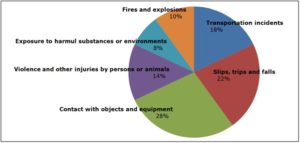

Fatalities in the CPI

My concern is primarily with process safety in the chemical process industries (CPI), for the employed and the self-employed alike. Process safety events—exposure to harmful substances or environments and fires/explosions—play a bigger role in fatalities in the CPI than in the workplace in general.

The BLS press releases focus on general concerns, but there is also detailed fatality census data available. The fatality rate for chemical manufacturing is 2.0 fatalities/100K FTE. The table on fatal injuries by industry by event gives a glimpse into the events that cause these fatalities in the CPI. Combining three NAICS classifications (324, 325, and 326), there were 57 fatalities in the CPI in 2015. While it should be no surprise that the distribution between events differs from that of the workplace in general, it may be surprise that process safety events still account for a relatively small proportion of the total.

Fatalities in the US CPI – 2015

Keeping Our Workplaces Safe

As a process safety professional, my focus is going to remain on process safety, on fires and explosions and on toxic releases. That’s what I do. All of us, though, have an interest in keeping our workplaces safe, whether from process safety hazards, general industrial hazards like falls and contact with objects, or from general hazards like transportation and workplace violence. A workplace fatality is a workplace fatality.

For those of you working in the CPI, continue to focus your attention on process safety but don’t lose sight of other hazards, all of which represent serious threats to your safety.

For those of you who are self-employed, take care. Not extra care, just the same care that the employed take. While you may not be compelled to comply with OSHA regulations, they were designed to keep people safe and you really want to be as safe as everyone else.

Mostly, though, let’s all keep working to improve, wherever those improvements can be made. Undoubtedly, we’ll go through periods where little improvement is made, but I still want to see us all continue to strive for a level of workplace safety that we can consider “safe enough.”